#Commoncore Part 2

Prologue

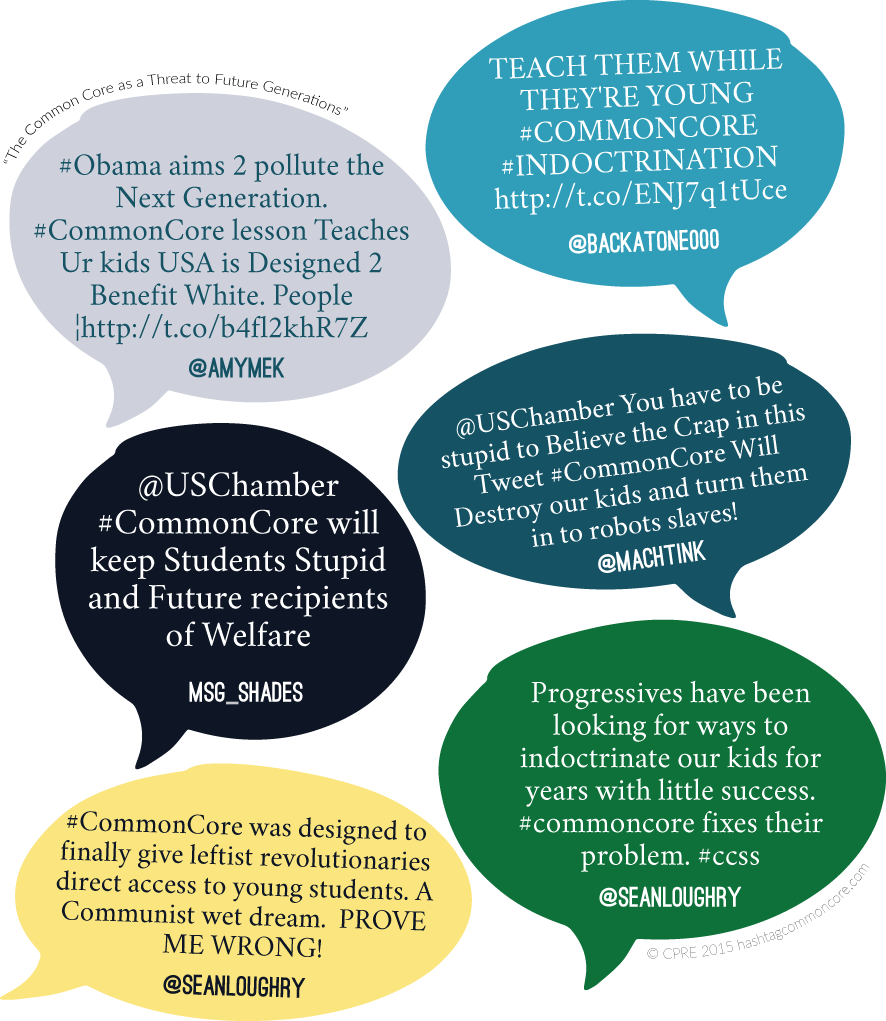

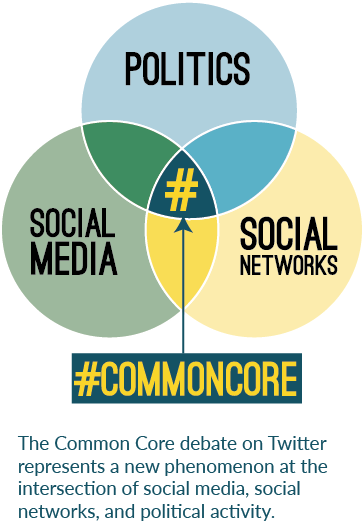

The Common Core has become a flashpoint at the nexus of education politics and policy, fueled by ardent social media activists. To explore this phenomenon, this innovative and interactive website examines the Common Core debate through the lens of the influential social media site Twitter. Using a social network perspective that examines the relationships among actors, we focus on the most highly used Twitter hashtag about the Common Core: #commoncore. The central question of our investigation is: How are social media-enabled social networks changing the discourse in American politics that produces and sustains social policy? To see how the site is organized, click HOW TO USE THIS SITE.

About the Project

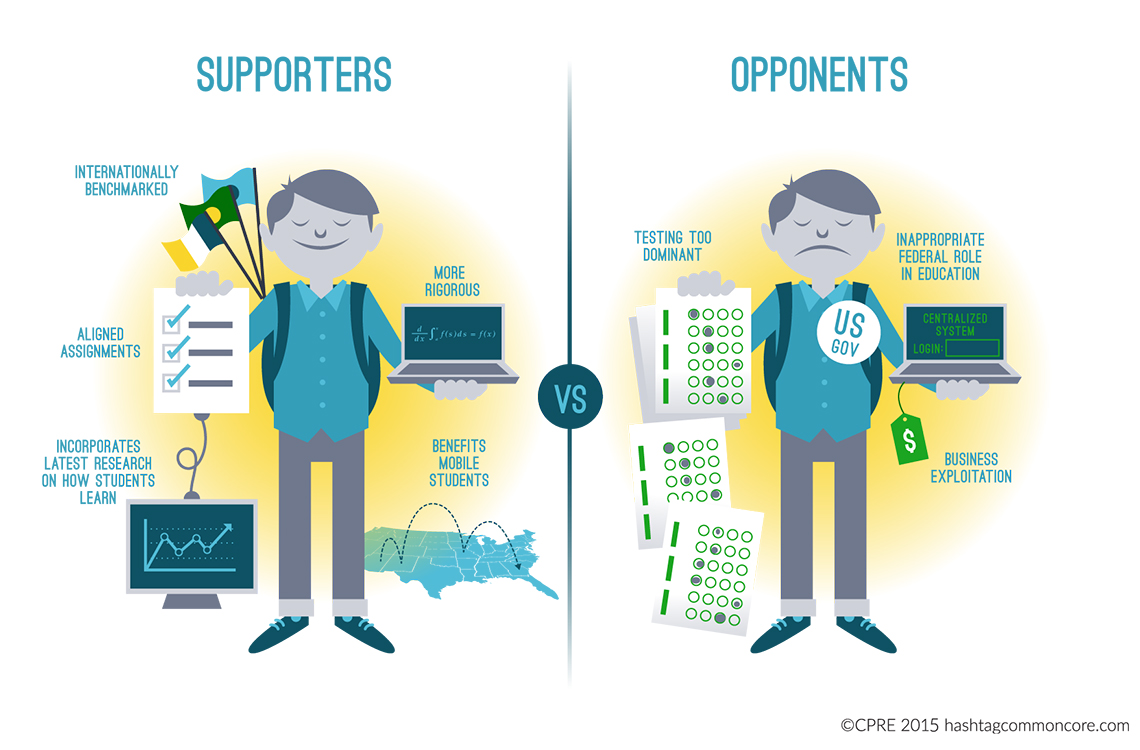

In the #commoncore Project, authors Jonathan Supovitz, Alan Daly and Miguel del Fresno, examine the intense debate around the Common Core State Standards education reform as it played out on Twitter. The Common Core, the major education policy initiative of our generation, seeks to strengthen education systems across the United States through a set of specific and challenging education standards. Once enjoying bipartisan support, the controversial Standards have become the epicenter of a heated national debate about this approach to educational improvement. By studying the Twitter conversations about the Common Core, we shed light on the ways that social media—enabled social networks are influencing the political discourse that, in turn, produces public policy.

The Rise of Social Media—Enabled Social Networks

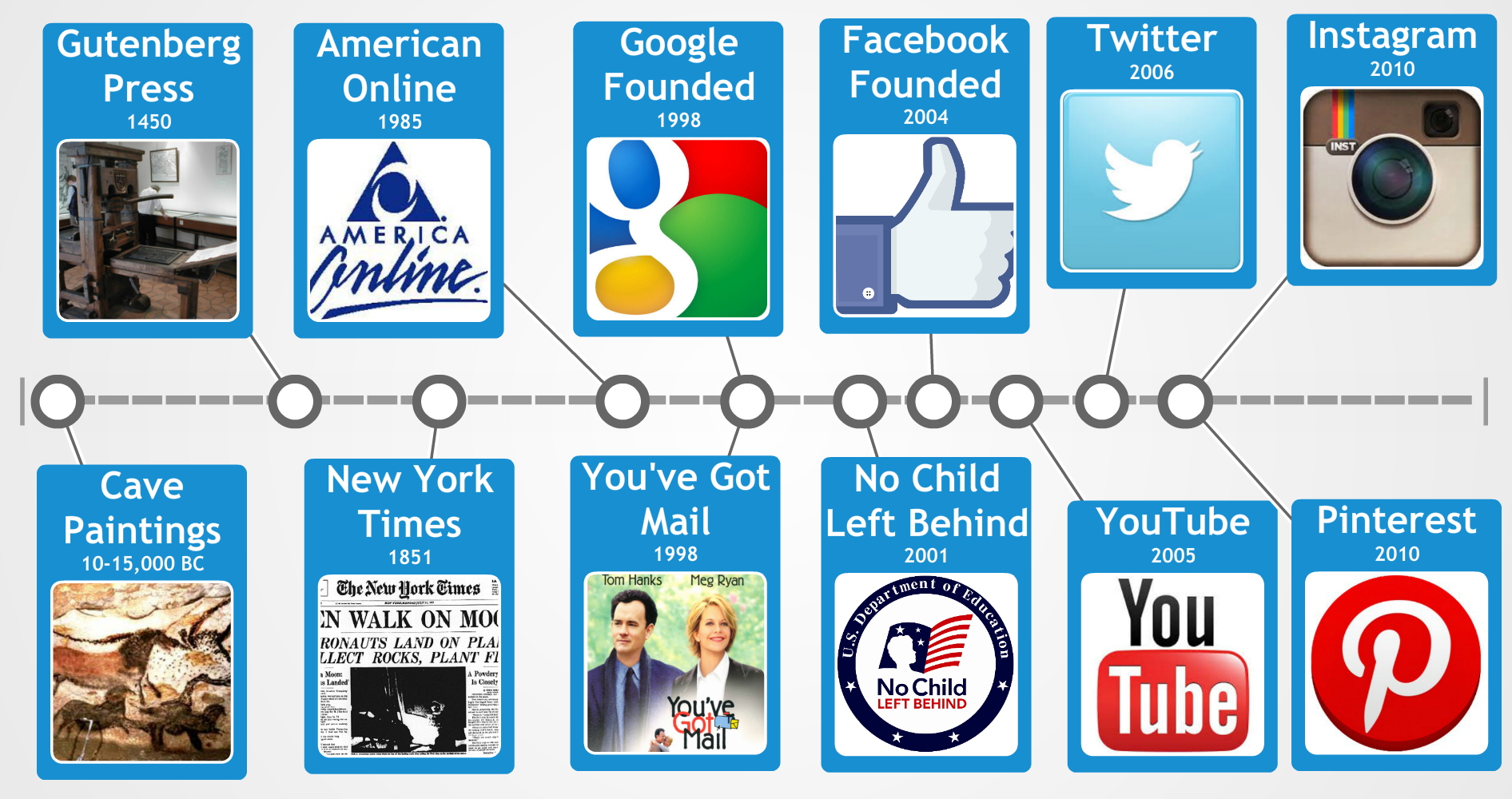

We live amidst an increasingly dense technology-fueled network of social interactions that connects us to people, information, ideas, and events which together inform and shape our understanding of the world around us. In the last decade, technology has enabled an exponential growth of these social networks. Social media tools like Facebook and Twitter are engines of a massive communication system in which a single idea can be shared with thousands of people in an instant.

Twitter, in particular, represents a compelling resource because it has become a kind of “central nervous system” of the Internet, connecting policymakers, journalists, advocacy groups, professionals, and the general public in the same social space. Twitter users can share a variety of media including news, opinions, web links, and conversations in a publicly accessible forum.

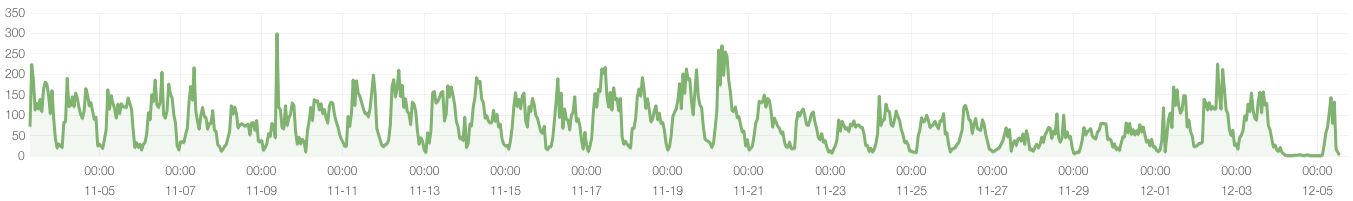

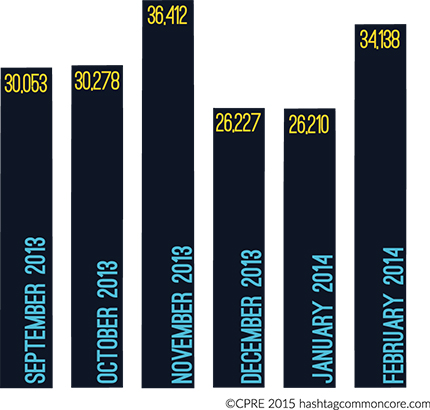

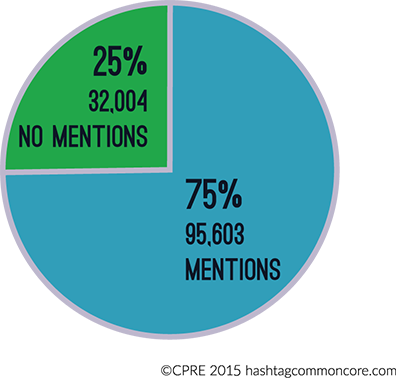

In this project we use Twitter to analyze the intense debate surrounding the Common Core State Standards. The Common Core has consistently generated a high volume of activity on Twitter. Hashtags (#) are used on Twitter to mark keywords or topics of interest to users, and one hashtag in particular, #commoncore, has consistently generated 30,000-50,000 tweets a month. While topics tend to trend and fall on Twitter, #commoncore has consistently maintained this volume of activity over the past 18 months and continues to be the most prevalent marker of conversations about the Common Core State Standards education reform.

Social Network Analysis Makes the Invisible Visible

To understand the #commoncore network, we use social network analysis as a lens to explore the ways that social media—enabled social networks are influencing the political discourse that produces public policy.

The powerful thing about social network analysis is that it makes visible the patterns of communication in social networks that are otherwise invisible to either those interacting within the networks or those observing them from the outside. Regardless of whether they are networks of neighbors talking across backyard fences or friend networks on Facebook, social networks are mostly invisible to the naked eye, similar to the way in which television signals are always flowing above and around us but we are generally oblivious to their presence. Despite being unseen, the ideas and messages transmitted via social media like Twitter can be very consequential in terms of the type, accuracy, and novelty of the information that is being broadcast, and with whom it is being shared. These sources help form our beliefs and opinions, and it is these convictions upon which our actions are based.

How Our Story Is Organized

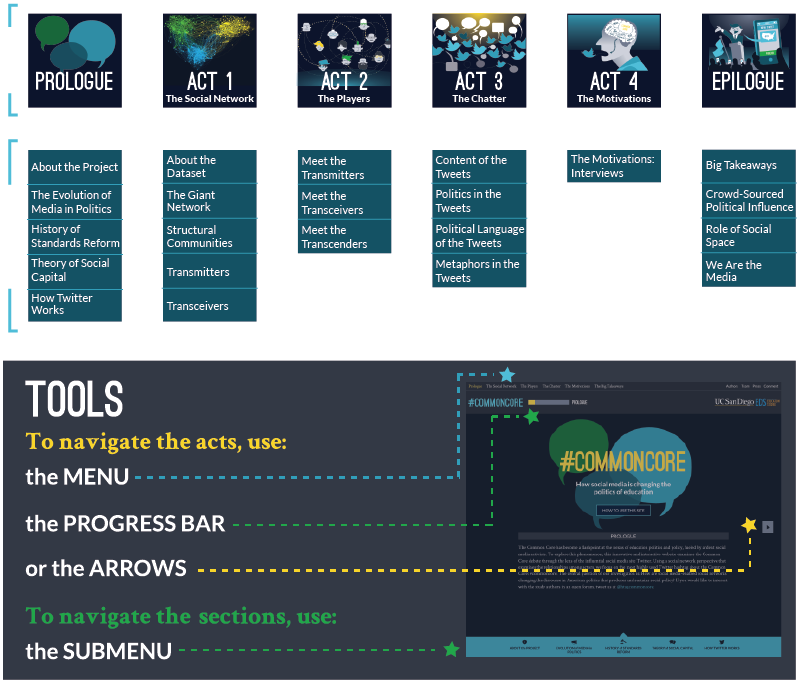

The story of the #commoncore communication system is organized into a prologue, four acts, and an epilogue:

- The Prologue is designed to give you a broad context for our investigation of the Common Core on Twitter. It includes this introduction to the project, as well as sections on the evolution of media in politics and the history of standards based reform. It also includes a short primer on the theory of social capital, which is the concept underlying the importance of social networks. The prologue also includes a short overview of how Twitter works for those unfamiliar with the social media tool.

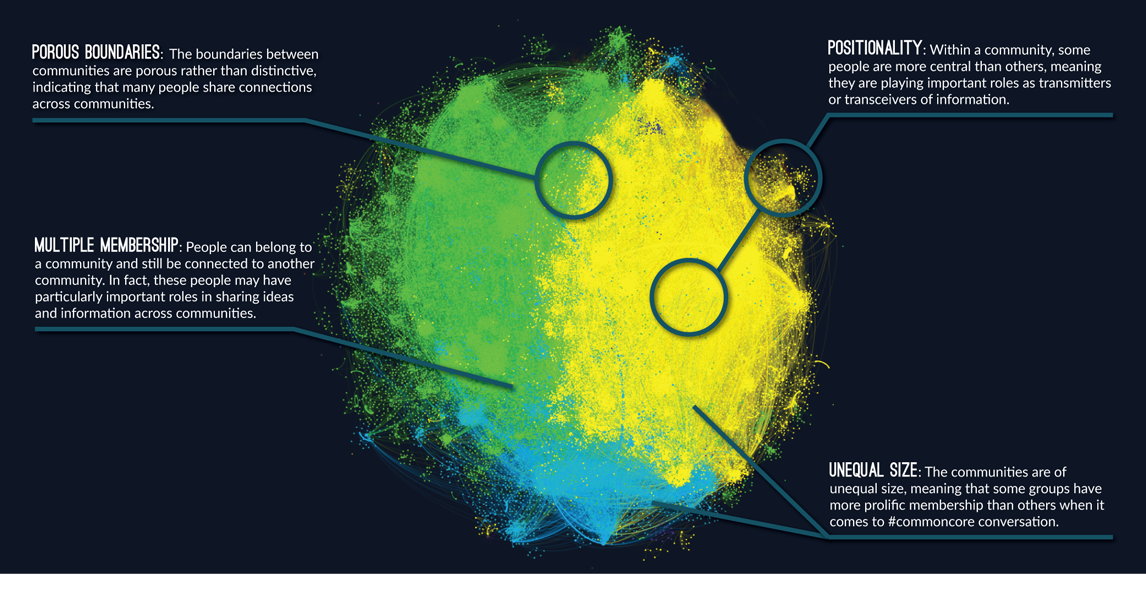

- Act 1 focuses on The Social Network and its subgroups. The act begins with a short overview of the data we analyzed for the project. We then introduce you to the giant #commoncore network and structural communities that are formed by their patterns of activity on Twitter. The structural communities are not our interpretation of the data, but are based upon actors’ actual choices and behavior on Twitter. The members of these subgroups have distinct characteristics and tend to share similar beliefs and opinions. We also introduce two types of influential actors on Twitter, transmitters, who send lots of tweets, and transceivers, whose messages are deemed so important that their communications are frequently re-sent and mentioned by others.

- Act 2: The Players introduces the particular key individuals and organizations in the #commoncore network. These include:

- The individuals who compose the Transmitter network, or those who send lots of tweets using #commoncore.

- The individuals who comprise the Transceivers network, or those whose tweets are frequently retweeted or mentioned by others, giving them a different kind of influence in the #commoncore network.

- The Transcenders, who are both high-frequency transmitters and transceivers. In the #commoncore network, these actors are the elite of the elite.

- Each of these types of players has an important role in the overall communication system. Their patterns of behavior offer insights into both the overall structure of the communication network and their positions within it.

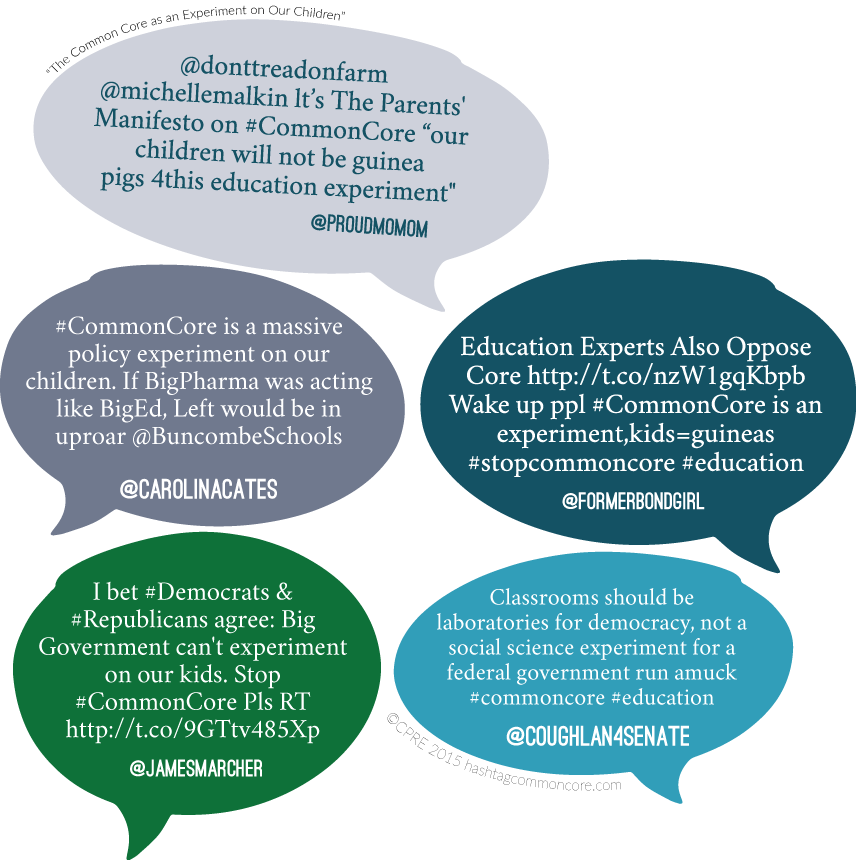

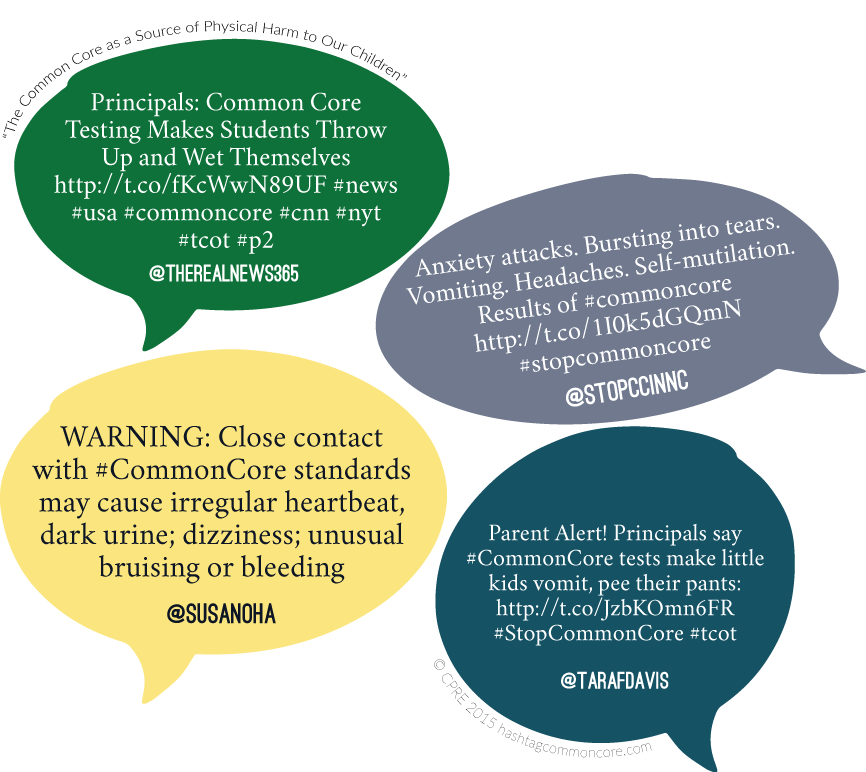

- Act 3: The Chatter hones in on the specific content of the #commoncore tweets of the key individuals introduced in Act 2. This act provides insight into the politics, opinions, and goals of the members of the network through analysis of the political language and metaphors they use in their #commoncore tweets.

- Act 4: The Motivations delves into the passions and deeply held beliefs of a small sample of prominent actors in the #commoncore network. It features audio interviews with some of the players, spotlighting their arguments for or against the Common Core as well as the motivations behind their social advocacy.

- The Epilogue distills the big takeaways from our exploration. It includes a summary of the key findings and essays about the meaning of the findings. Jonathan Supovitz’s essay examines the rise of crowd-sourced political influence represented by the #commoncore phenomenon. Alan Daly considers larger questions of the role of social space in public debate. And Miguel del Fresno writes about the ongoing innovative disruption of social media.

Funding

This project received no external funding from any source.

About the Authors

The creators of the #commoncore Project are:

- Jonathan Supovitz, the co-director of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education and a Professor of Education Policy and Leadership at the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Alan Daly, the Chair of the Department of Education Studies and a Professor of Education at the University of California, San Diego.

- Miguel del Fresno, a lecturer at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) in Madrid, Spain and a senior communication consultant and researcher.

Citation

Supovitz, J., Daly, A., & Del Fresno, M. (2015, Feb 23). #commoncore Project. Retrieved from http://www.hashtagcommoncore.com

The Evolution of Media in Politics

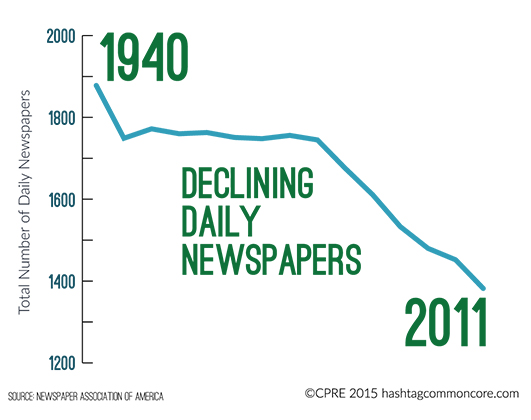

The role of the media in shaping political opinion has changed dramatically over the past 60 years, as the populace has grown both more sophisticated and more fragmented. Before World War II, radio and newspapers were the dominant forms of mass communication. Franklin Roosevelt’s famous fireside chats were a central means of messaging, and newspaper circulations were at an all-time high. In the 1950s, researchers Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz observed that mass media influenced opinion leaders, who in turn influenced their followers, the general public.1 They called this process the two-step flow model to indicate that public opinion was developed through a cascading process.

As network television became more dominant in the 1960s and 70s, the three major networks—CBS, NBC, and ABC—molded public perceptions to an unprecedented degree in what became known as agenda setting. In one famous study that was replicated many times, McCombs and Shaw2 demonstrated the overwhelming alignment between what residents in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, thought were the most important election issues of the day and what the news media reported were the most important issues. The public depended heavily on the three dominant networks to stay abreast of national and international news, and because of this, the media had tremendous influence in molding public opinion.

Proliferation of Media Outlets

With the advent of cable television in the 1980s, the proliferation of channels led to a fragmentation of audiences. Cable news, talk radio, and 24-hour all-news outlets competed for attention with increasingly brazen and partisan reporting. The wide array of available media choices caused audiences to increasingly fracture as people tended to avoid information that diverged from their worldview, instead seeking out information that was consistent with their preexisting attitudes and beliefs.3 In this context, it is not hard to see why many political scientists have argued that the expansion of available news sources has increased political polarization.4

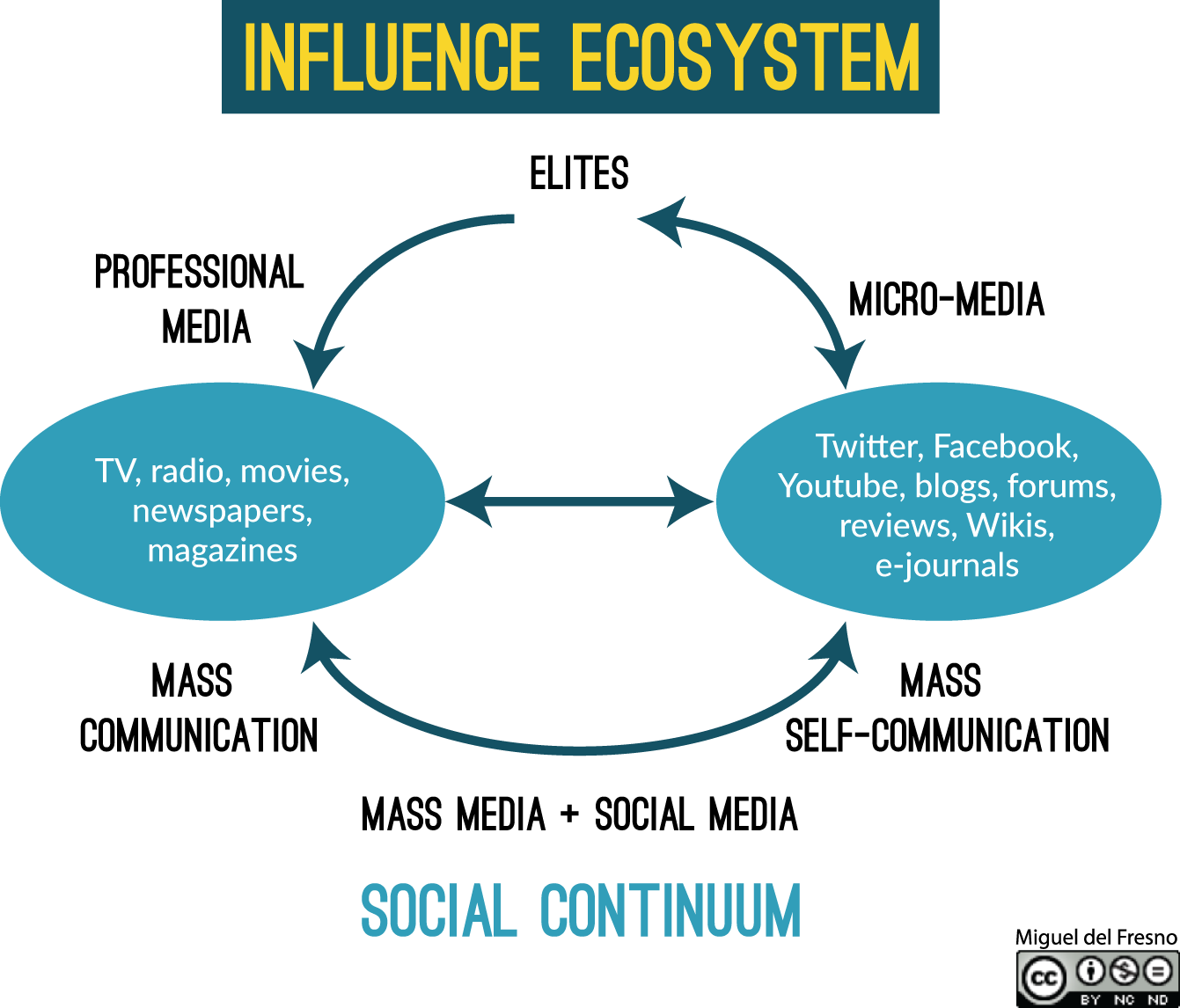

In today’s media landscape, the Internet and social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook provide even more opportunities for audiences to splinter as members with similar views have increasing access to each other. And there are some distinct differences between the media landscape at the end of the last century and the social media era we are in today. The growth of cable television in the 1980s and 1990s was still essentially unidirectional from “elites” to general audiences because of the content control of mass media and passive forms of viewing. Social media, however, allows members to actively voice their opinions and engage directly with each other.

Some researchers, including Valenzuela, Park, and Kee, view social media as a new opportunity for political participation, free flow of information, and broader democratic mobilization.5 Others, like Roodhouse, view social media sites as nothing more than discursive information flows and echo chambers where the fervent can shout with each other.6

Thus, Twitter is in many ways the perfect platform for examining the ways in which social media are influencing the Common Core conversation in the United States. Twitter is a free, online, and global communication network that combines elements of blogging, text messaging, and broadcasting. One of the most valuable aspects of Twitter is its evolving nature to be, “a media of intersection of every media and medium.”7

References

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. & Katz, E. (1955). Personal influence . New York: Free Press.

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly , 36 (2), 176-187.

- Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative vs. participatory democracy . New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58(4), 707-731.

- Valenzuela, S., Park, N., & Kee, K. F. (2008). Lessons from Facebook: The effect of social network sites on college students’ social capital. In 9th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX . Retrieved from https://online.journalism.utexas.edu/2008/papers/Valenzuela.pdf

- Roodhouse, E. A. (2009). The voice from the base(ment): Stridency, referential structure, and partisan conformity in the political blogosphere. First Monday, 14 (9).

- Dorsey, J. (2012). “Twitter takes the pulse of the planet. It’s the intersection of every media & medium,” Twitter, November 15, 2012. Retrieved from http://twitter.com/TwitterAds/status/269129576318386177

The Recent History of Standards Reform in America

The Common Core State Standards in mathematics and English language arts were developed at the behest of the group of organizations led by the National Governors Association (NGA) and the Council Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The Standards set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level. The development of these standards began in 2009, but they are part of a history of several decades of education reform.

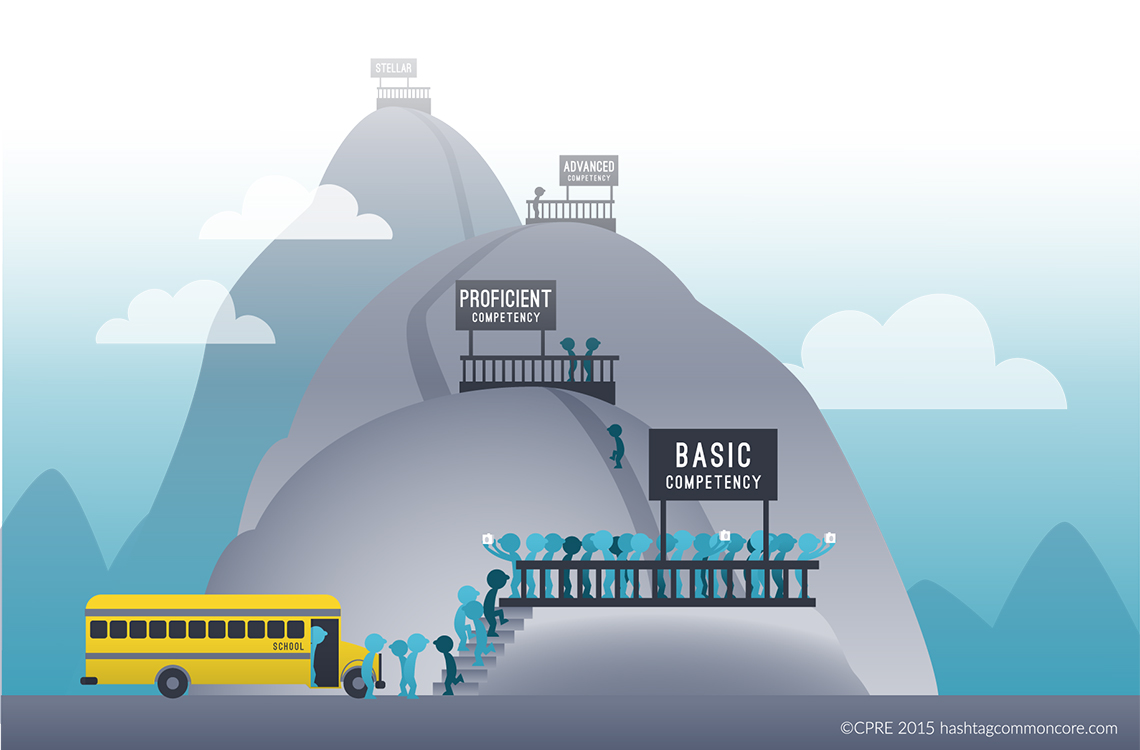

1980s: Focus on Minimum Competency Testing

In the 1980s, policymakers created a set of minimum competency tests, which they intended schools to use as a foundation for performance. The expectations codified in the tests focused on a set of basic skills that schools were expected to have all students meet. However, the basic expectations assessed through the minimum competency tests often became the aspirations for instruction. The important lesson from this era was that low expectations produced low performance.

1990s: Statewide Systemic Reform

The apparent “race to the bottom” phenomenon spurred by minimum competency testing led to an emphasis on high expectations. The systemic reform effort of the 1990s was built around three general principles. First, ambitious standards developed by each state would provide a set of targets of what students ought to know and be able to do at key grade junctures. Second, states measured progress toward standards by developing aligned assessments that combined rewards and sanctions for holding educators accountable to the standards. The third component was local flexibility in organizing capacity to determine how best to meet the academic expectations.1 This structure of clear goals (standards), measures (assessments), and incentives (accountability) at the state level, combined with implementation autonomy fit with our historical conceptions of education as a local effort. This led each state to develop its own standards and assessment systems, which produced lots of variation in the quality and rigor of state educational systems across the country.

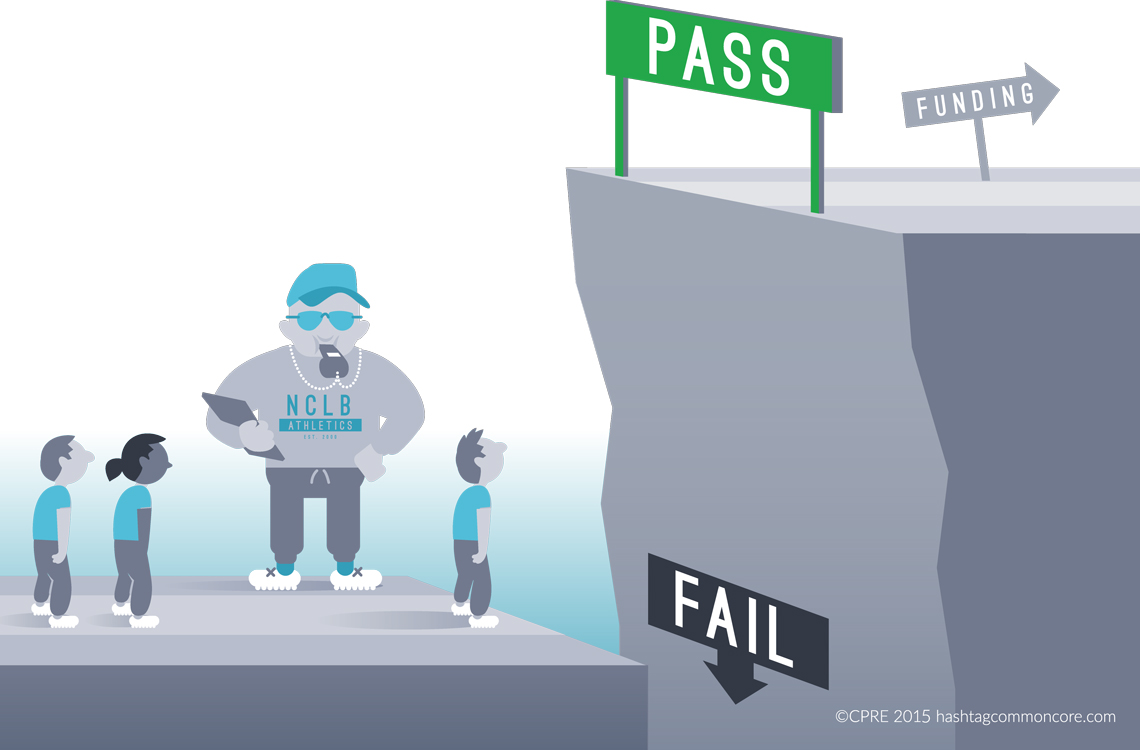

2000s: Test-Based Accountability

The 2000s gave rise to the era of test-based accountability in education. The 2001 passage of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act inaugurated an expansion of testing by requiring states that received federal funding to assess students in all grades between third and eighth, and one year in high school. NCLB pressed states to develop plans to have all schools make adequate yearly progress with a target of 100% proficiency by 2014—an endeavor that would prove to be impossible. The NCLB legislation also required states to disaggregate school results by subgroups, in an effort to prevent districts and schools from hiding disparities in performance within overall averages. This movement can be seen as an attempt to tighten the linkages in the theory of standards-based reform by increasing student performance expectations via high-stakes testing to hold schools accountable for meeting standards.

Research on schools pressed by test-based accountability showed both productive and unproductive responses. There was an increase in attention to tested subjects, a rise in test preparation behavior, more attention to students just at the cusp of passing the test, and greater attention to heretofore marginalized students.2

Some states also gamed the system by creating tests that most students could easily pass. There were also several cases of systematic cheating by educators in school districts and schools that made national headlines. The accountability emphasis of No Child Left Behind left many policymakers convinced that although pressure was important, we couldn’t just squeeze higher performance out of the system—we had to build a structure to support it.

2010s: “Common Core State Standards”

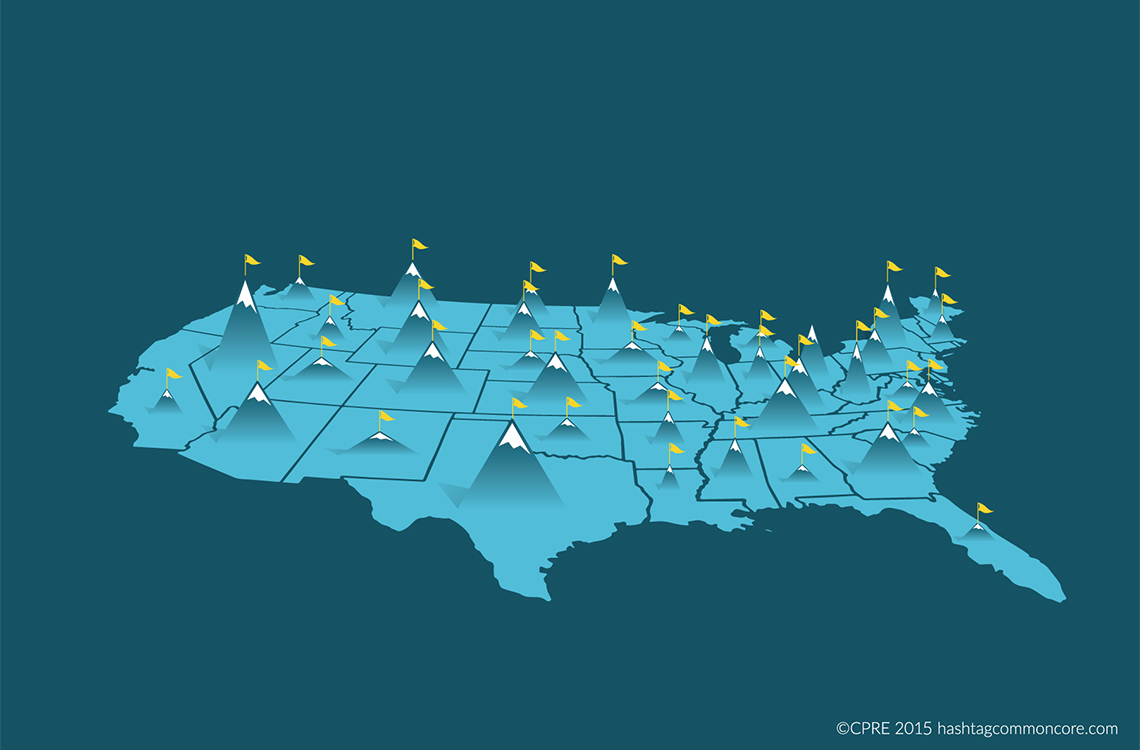

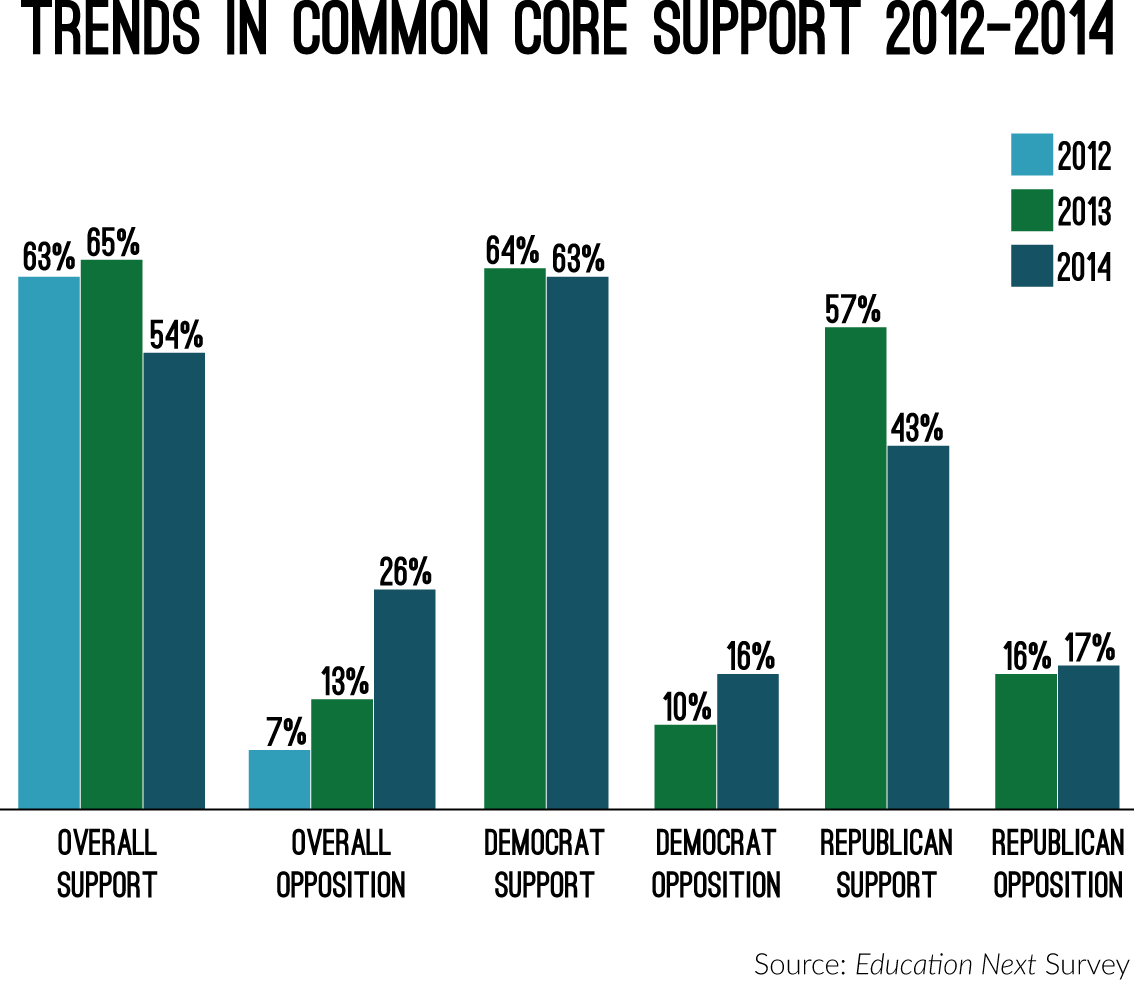

This brings us to the present major reform initiative in the United States - the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The CCSS set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level from Kindergarten to 12th grade. In a remarkable moment of bi-partisanship, the CCSS were adopted by the legislatures in 46 states and the District of Columbia in 2010. Alaska, Texas, Virginia and Nebraska did not adopt the Common Core, preferring their own state standards. Minnesota adopted the Common Core ELA standards, but not those in mathematics. Since then, the CCSS have become remarkably political and several states have either backed away from the CCSS and/or the associated tests or are in the midst of heated discussions about their involvement with the CCSS.

The CCSS incorporate a number of lessons learned from the earlier standards-based reform movement. The new standards were named the “Common Core” because they were intended to eliminate the variation in the quality of state standards experienced in the past. The experience of the 1990s taught us that not all standards are equal. The new experiment with common state standards was done to avoid the previous problem of differing quality of standards and their accompanying student assessments. —They were developed at the behest of the state governors and chief state school officers to avoid the charge of federal intrusion—which came nonetheless after the Obama administration advocated for standards in the Race to the Top funding competition and provided the financing for the Common Core testing consortia. Similarly, the Common Core testing consortia of Smarter Balanced and Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) were funded to create assessments aligned with the standards. Thus, there was a push for a uniform set of standards and the development of aligned assessments to build a more coherent system for educational improvement.

In sum, many factors led to the development of the Common Core State Standards. Ever since the Nation at Risk Report of 1983, which famously stated "the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people,” we have felt our education system besieged.3 Flat longitudinal performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and middling performance on international comparative assessments like TIMSS and PISA has further perpetuated the belief that America needs a more rigorous education system to compete with other nations in the increasingly global economy. This middling performance is often partly attributed to the spiraling nature of what is taught in America’s schools, a student experience that has been called “a mile wide and an inch deep.”4

Thus, the Common Core represents the latest response to the challenge of educational improvement by incorporating the lessons learned from prior experiences with education reform. The minimum competency era taught us that we needed high expectations for all students. The state-wide systemic reform movement of the 1990s taught us that state-led standards and testing systems would produce too much variability in quality and alignment. The decade of experimentation with test-based accountability drove home the lesson that, while accountability pressure was important, we couldn’t just squeeze higher performance out of the system without a coherent infrastructure to support it. All these factors have led to the push for a more comprehensive system with a uniform set of standards and aligned assessments that would allow for consistency in an increasingly mobile society.

References

- Smith, M. S., & O'Day, J. A. (1991). Systemic school reform. In S. H. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing: The 1990 yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (pp. 233-267). New York: Falmer Press.

- Hamilton, L. (2003). Assessment as a policy tool. In Robert Floden, (Ed.) Review of Research in Education, 27, 25-68.

- Gardner, D. P., Larsen, Y. W., Baker, W., & Campbell, A. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Schmidt, W. H., McKnight, C. C., Houang, R. T., Wang, H., Wiley, D. E., Cogan, L. S., & Wolfe, R. G. (2001). Why schools matter: A cross-national comparison of curriculum and learning. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Theory of Social Capital

A Relational Perspective

This project is based on the fundamental idea that connections and ties between individuals create a larger network, and that this network is important to outcomes at both the individual and collective level. Ideas, opinions, and information that flow through these ties can be influential and impact behavior.

This is idea is grounded in social capital theory, which posits that individuals exist in a social structure of relationships. This structure of relationships facilitates or inhibits an individual’s access to both physical and intellectual resources such as knowledge, ideas, and opinions. Social capital theorists consider the richness of a social network to be a key component of a group’s social capital, which refers to the kinship, trust, and goodwill that provides a collective advantage to the community.1

Sociologist Robert Putnam has chronicled the social benefits of memberships in organizations such as churches, clubs, and more.2 He hypothesized that the benefits he observed were due to the connections that these groups offer to their members. In another famous example of the importance of social capital, Mark Granovetter found that extended ties even beyond one’s tight-knit circle of friends helped people gain access to job opportunities.3

Historical Grounding

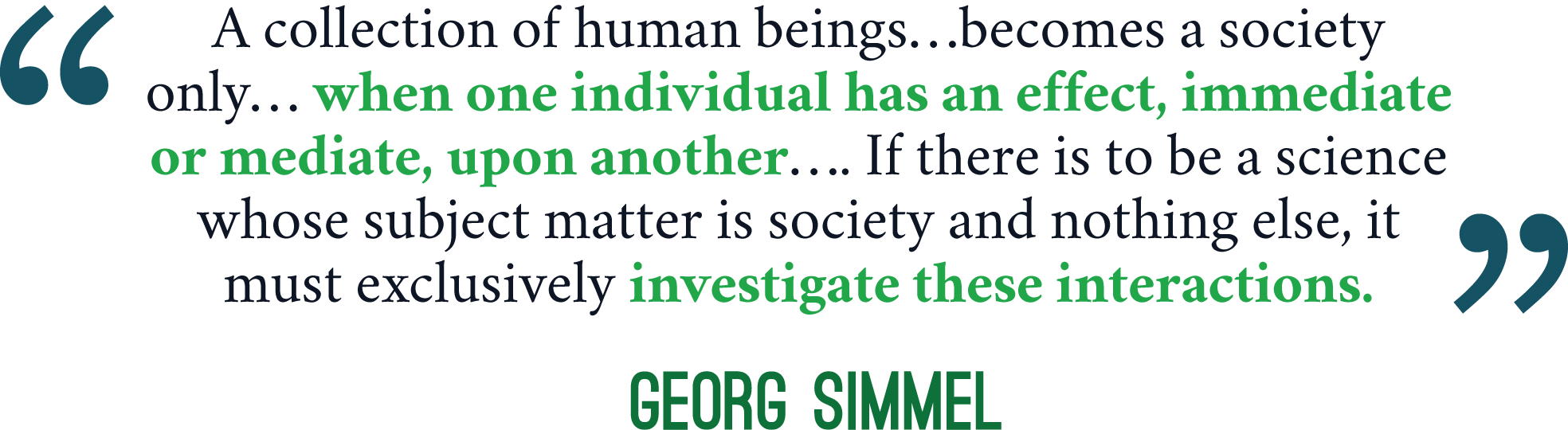

The most explicit and earliest network approach to society dates back to German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858-1915) who wrote, “Society exists where a number of individuals enter into interaction,” and the object of study “was no more and no less than the study of the patterning of interaction.”4

Contemporary social network analysis was formalized in the 1930s with the work of Jacob Moreno, who studied runaway girls and argued that their behavior was influenced by the social links among them.5 Moreover, the girls themselves may not have been consciously aware of how their actions were socially influenced and how, ultimately, it was their position in a social network that may have affected the runaway behavior. This idea is still prominent today and has expanded to the idea that social influence can impact a host of behaviors—both consciously and unconsciously—from happiness to weight gain to access to career opportunities.

Moreno's sketch of the cabins of runaway girls.

Moreno’s early drawings of the cabins in which the runaway girls stayed and the relationships among the girls were some of the earliest depictions of social networks. The larger circles are cabins and the smaller circles depict the initials of runaway girls. The lines represent connections between girls. This was one of the earliest sociograms is an example of state-of-the-art infographics from the 1930s.

Thus, a core idea of the work running from Simmel to Moreno to Coleman to Putnam is the importance of social networks, which reflect the overall structure of small and large societal relationships. This idea comes with some basic assumptions.

Assumptions Underlying the Social Network Perspective

There are a few core theoretical underpinnings to a social network perspective including:

- Actors in a network are assumed to be interdependent rather than independent.

- Relationships are regarded as conduits for the exchange or flow of resources and influence.

- The robustness and structure of a network has influence on the resources that flow to and from an actor and across a network.

- Patterns of relationships present dynamic tensions as these patterns can act as both opportunities and constraints for individual and collective action.

This approach privileges the structure of relationships to hold more sway than the attributes of individual actors. For our work, we start with a structural perspective and then add individual attributes and perspectives. Let’s look a bit more into what a network can illuminate.

Comparing Formal and Informal Networks

One of the most interesting aspects of social networks is the ability to compare and contrast the formal structure of relationships—meaning how things are formally structured versus how people actually interact. Sometimes, formal professionals are less important in social networks while unofficial individuals are central. In this example, a central player (large red box) in the formal system (left) is at the top of the hierarchy, yet in the informal social structure (right) this actor is marginalized (average-size red dot). Social network analysis can sometimes make the invisible visible.

Networks are Everywhere

Networks are intuitive and show up in many aspects of our lives. They may be structural, like subway systems or computer connections, or social, like relationships with our friends, church members, sports teams, parent groups, or colleagues.

From a social network perspective, individuals or organizations can have relationships that are depicted by lines connecting them, called ties. These ties can be uni-directional (going in one direction or the other) or bi-directional. Ties that go out (i.e. are sent) from one actor to another are called out-ties and ties that come in (i.e. are received) are referred to as in-ties. Ties can sometimes be reciprocated. These can be seen in the informal social structure graphic above.

The size of the circle that represents each individual, called a node, reflects the magnitude of the resource of that individual or group. Some actors have more “importance” in the network, meaning they have more incoming or outgoing ties in comparison to others. Other actors are more peripheral and others are even entirely disconnected from the network (called isolates).

Central Actors

The major actors in a network are considered central because they have more connections than others. These individuals therefore amass disproportionately more resources through unique social links and, therefore, may have undue influence over a network.

Research suggests that these actors also have access to novel and diverse resources, allowing them the possibility to guide, control, and determine the flow of resources to others in a group.6 In this sense, they often disproportionately dominate what information and opinions get moved across a network.

In this project we are most interested in those individuals who occupy a central location in a network, as central actors have been shown to influence other actors and interactions in a social sphere. We are specifically interested in actors who transmit a high number of messages to central actors in the network. We call these individuals transmitters. We are also interested in those actors who both receive and relay a large number of messages to others in the network. We call these individuals transceivers. Both of these types of central actors are important in understanding how resources flow in a network.

Other Actors in the Network

Although our project focuses on central actors, it is also important to consider how those central actors may influence others in the network who are considered more peripheral. More peripheral actors are typically engaged in fewer interactions and, as such, may have limited access to resources and tend to have less influence over the larger network. The perspectives of peripheral or isolated actors may not be as readily spread across a network and information may take longer to make it their way.

References

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 68.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 1360-1380.

- Simmel, G., quoted in Freeman, L.C. (2004). The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science. Vancouver, BC: Empirical Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who shall survive? Foundations of sociometry, group psychotherapy and sociodrama. New York: Beacon House.

- Daly, A .J., Finnigan, K, Jordan, S., Moolenaar, N. & Che, J. (2014). Misalignment and perverse incentives: Examining the role of district leaders as brokers in the use of research evidence. Educational Policy, 28(2), 145-174.

How Twitter Works

Founded in 2006, Twitter is one of the top 10 most-visited websites on the Internet, with over 645 million users worldwide. Twitter is often called a micro-blogging social network site, where users can sign up for free, display recognizable user profiles, share messages with those who chose to follow them, and receive the messages of those they follow. Twitter users are a special breed of communicators—they represent only 18% of Internet users and 14% of the overall adult population. According to Pew Research from 2014, they are more affluent, younger, and more ethnically diverse than the general population.1

Each Twitter message can contain not more than 140 characters, including spaces, which is exactly the number of characters in this sentence. While some view the brevity of tweets as a shortcoming of the medium, others view the minimal effort as an advantage.2 Additionally, given the concise nature of the medium, Twitter users get quite creative with the construction of their tweets, and often link people to other Internet locations, including articles, blogs, and other websites.

Communicating with Twitter

An important feature of Twitter is the way that the medium is designed for people to communicate. Twitter users can follow others on the medium, be followed, or have a reciprocal relationship.

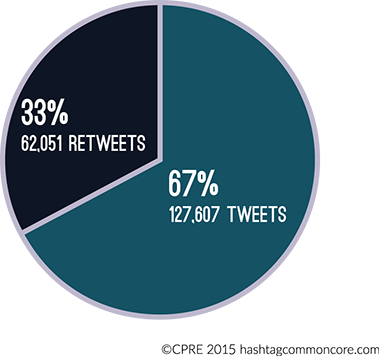

Twitter users can send their messages in three ways. First, they can initiate messages, called tweets. Second, tweets can be further disseminated when recipients repost them through their account. This technique, called retweeting, refers to the verbatim forwarding of another user’s tweet. A third type of messaging is a variant of tweeting and retweeting, called mentioning. Mentions include a reference to another Twitter user’s username, also called a handle, denoted by the use of the “@” symbol. Mentions can occur anywhere within a tweet, signaling attention to that particular Twitter user. All three of these approaches are powerful because they can introduce information to new audiences.3

Conversations are facilitated by preceding a tweet with the ‘@’ sign and a user’s name (i.e. @BenFranklin). Such messages are not private, but can only be seen by those who have reciprocal relationships (i.e. are following and followed) by both the sender and receiver of the targeted tweet. If, however, the @ is preceded by a period (.@), the conversation is visible to all members of either parties network.

Hashtags

Twitter users employ the hash or pound sign (#) to identify, or tag, messages about a specific topic. Twitter streams are searchable by hashtag, which is the basis for our research on the #commoncore.

Followers and following

An important distinction on Twitter is the directionality of messaging. Some users are primarily senders, or transmitters, of messages. These transmitters are influential if they have many followers who receive their messages. Some people, like celebrities and politicians, are transmitters who are followed by many people, but follow relatively few others.

Other Twitter users are primarily followers, or receivers, of messages. These followers are recipients of tweets, but do not share this information.

Still other Twitter users are transceivers, both senders and receivers of messages. These individuals are the audience to some and the main attraction to others. These individuals gain their influence as conduits in the flow of information.

In our analyses, we are primarily interested in transmitters and transceivers.

Reciprocity

Twitter can be used in ways that are both uni-directional and bi-directional.

If two individuals follow each other, they both receive each others’ tweets. This creates a reciprocal relationship.

Information contained in Tweets

Tweets can be used to:

- Share information or news

- Express opinions

- Provide links to other web sources

- Carry a conversation

Another dimension to consider when studying the Twitterverse is the accuracy of the information that is disseminated. Because posts are self-policed, there is no external check on the veracity of data one receives on Twitter. A study of news headlines by Schmierback and Oeldorf-Hirsch found that headlines presented on Twitter were significantly less credible than the same headline on the news sites themselves.4 Other studies have shown that most Twitter messages regarding news events are accurate, but the medium is also used to spread misinformation and false rumors, often unintentionally.5 In such an environment, the reputation of the sender of the message is a crucial component of its perceived credibility.

References

- Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Himelboim, I. (2014). Mapping Twitter topic networks: From polarized crowds to community clusters. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/02/20/mapping-twitter-topic-networks-from-polarized-crowds-to-community-clusters/

- Zhao, D., & Rosson, M. B. (2009). How and why people Twitter: the role that micro-blogging plays in informal communication at work. In Proceedings of the ACM 2009 international conference on Supporting group work , 243-252. DOI=10.1145/1531674.1531710

- Boyd, D., Golder S, and Lotan G (2010). Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on Twitter. HICSS-43 . Kauai HI: IEEE.

- Schmierbach, M., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2012). A little bird told me, so I didn't believe it: Twitter, credibility, and issue perceptions. Communication Quarterly , 60 (3), 317-337.

- Castillo, C., Mendoza, M., & Poblete, B. (2011). Information credibility on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 20th international conference on World wide web , 675-684. DOI=10.1145/1963405.1963500

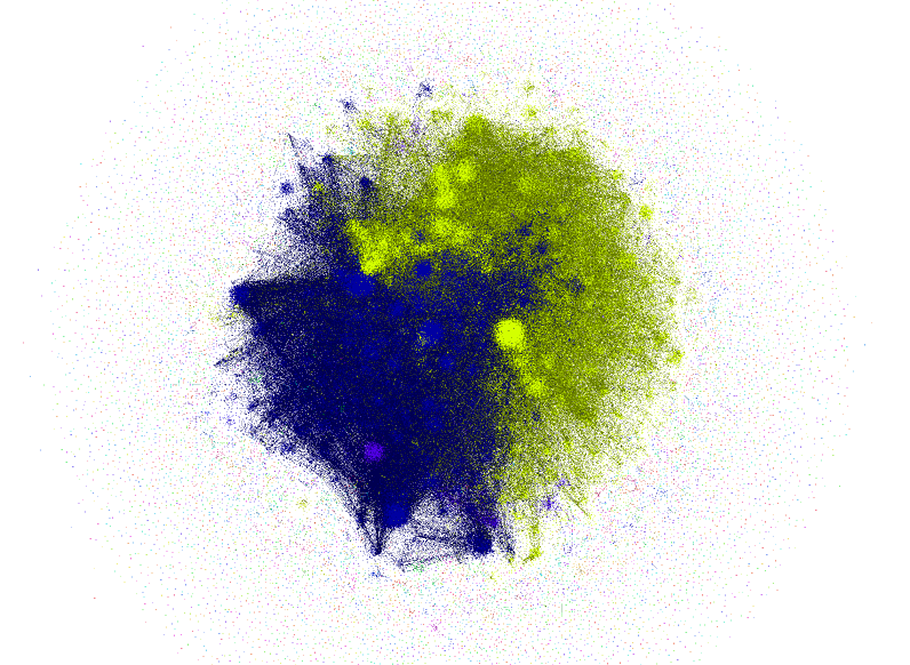

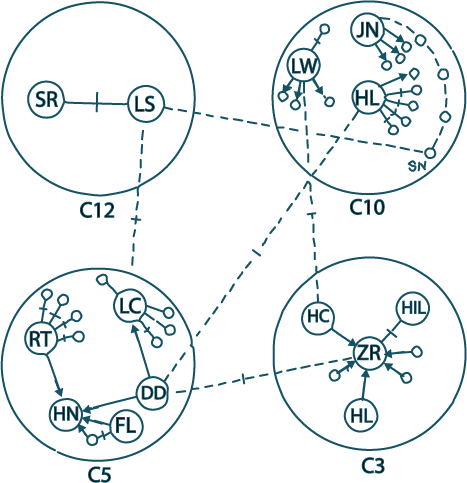

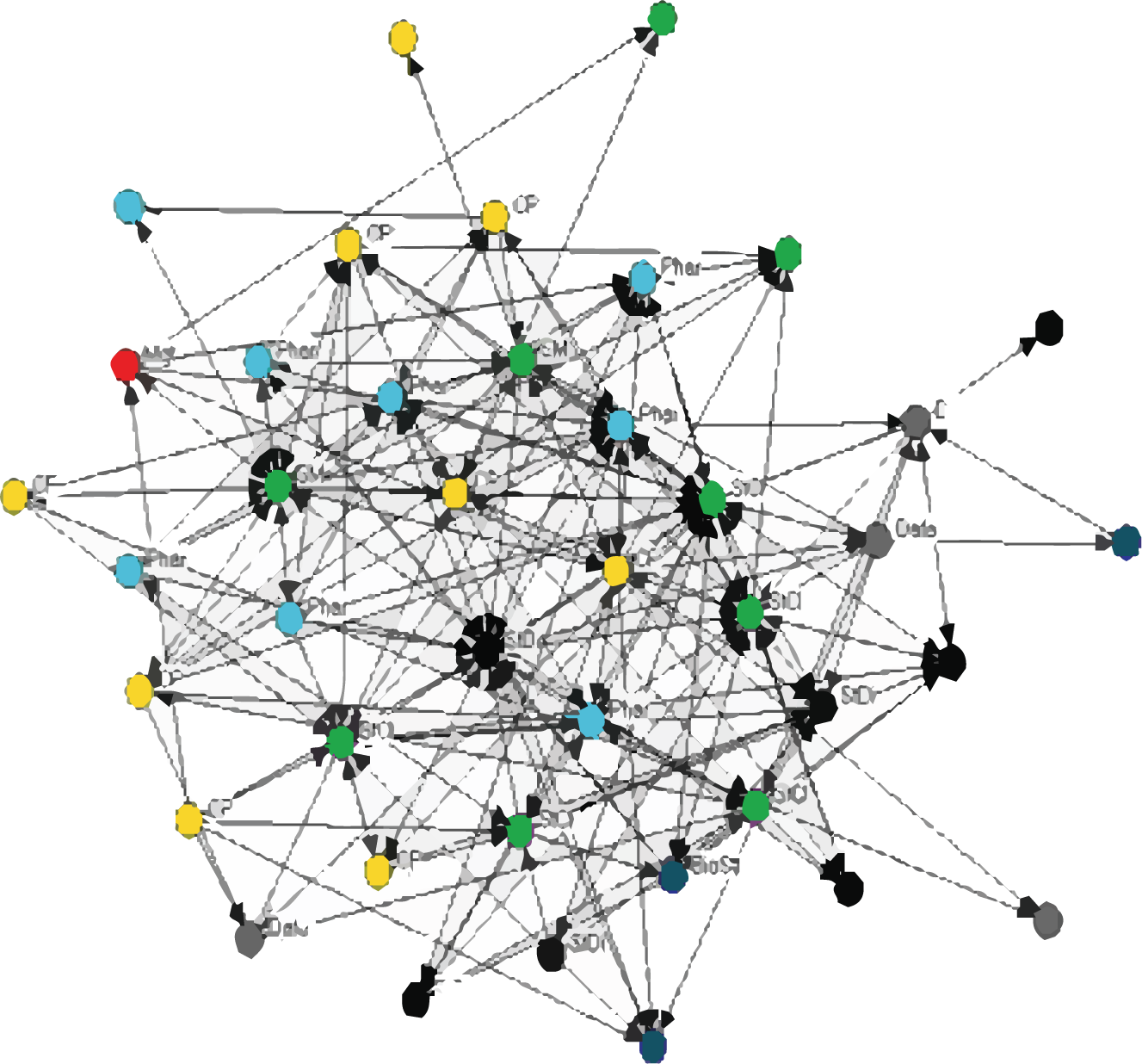

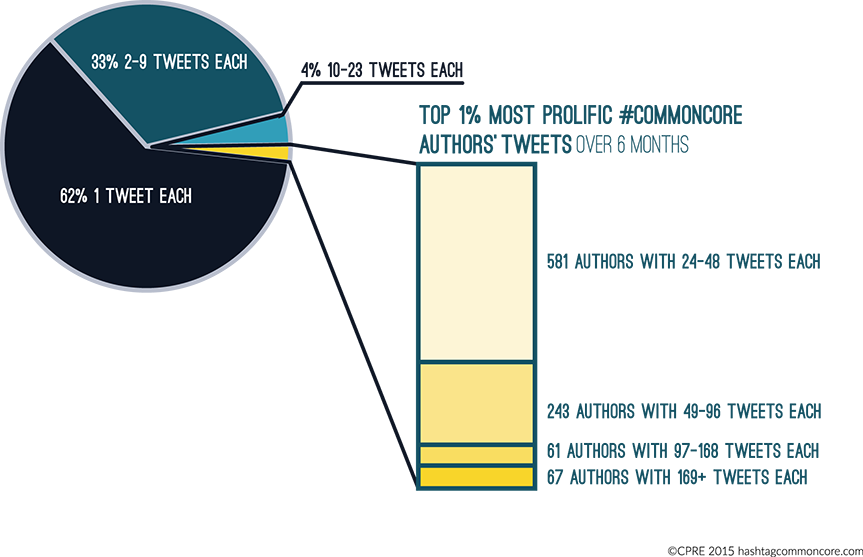

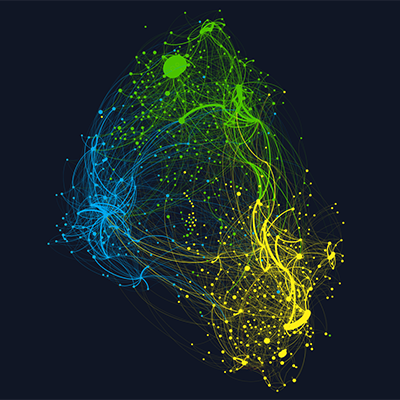

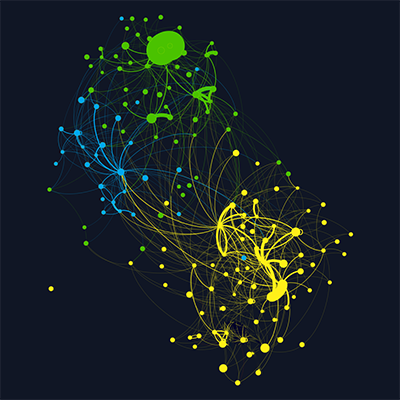

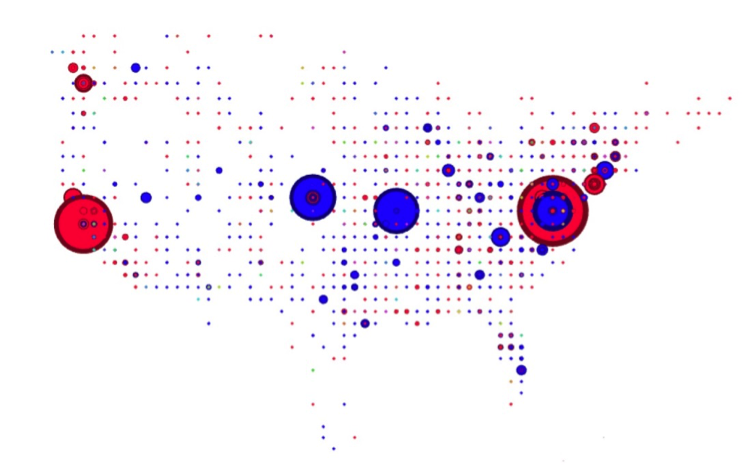

These graphic shows the top 1% of transceivers in the #commoncore network. These are users whose messages are retweeted and/or they are mentioned by others a relatively large number of times. There are about 650 transceivers in the 1% network. These actors are central to the network because of their role as reverberators of information. In this way, they play the crucial role of having information that is spread about #commoncore across the Twitter network.

These graphic shows the top 1% of transceivers in the #commoncore network. These are users whose messages are retweeted and/or they are mentioned by others a relatively large number of times. There are about 650 transceivers in the 1% network. These actors are central to the network because of their role as reverberators of information. In this way, they play the crucial role of having information that is spread about #commoncore across the Twitter network.

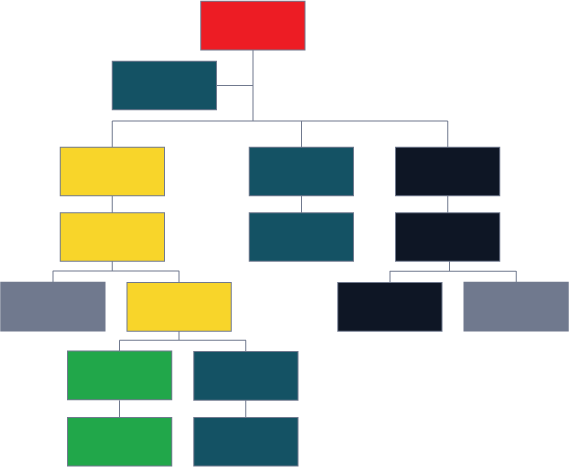

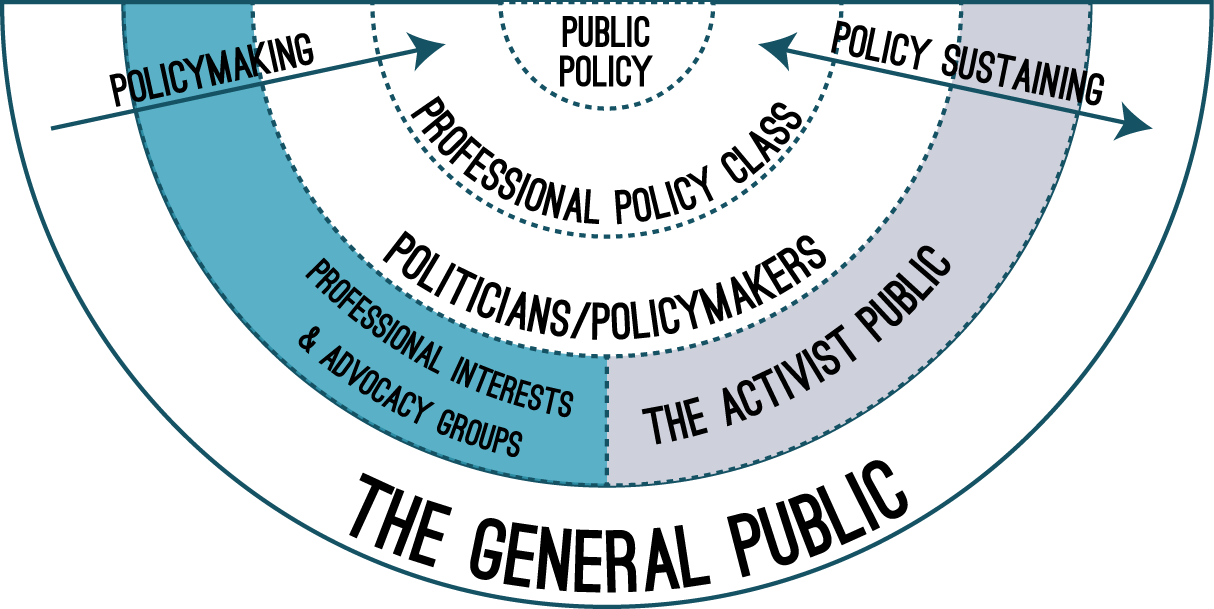

In the figure to the right, I depict the different groups that contribute to making public policy, at the center of the image. Layered closest to policy are professional policymakers, who may be policy staffers, or career legislative assistants who actually craft the details of a policy itself. Depending on the complexity of the policy, this group may or may not play a major role in policymaking. Adjacent to them are politicians who, once elected, are the creators of policy. The next (shaded) ring, contains advocates who either support or oppose a policy, or who desire a particular rendition of a policy. I have highlighted this ring because it contains the main actors of the #commoncore story, and I will return to it in a moment. The final ring of the semi-circle is the general public. The rings are depicted as dotted lines to signify that the relationships and flow of information among these layers of the process are porous. All of these rings together contribute to the policy making process, for they all exert pressure and inform the development of policy in different ways and by different means.

In the figure to the right, I depict the different groups that contribute to making public policy, at the center of the image. Layered closest to policy are professional policymakers, who may be policy staffers, or career legislative assistants who actually craft the details of a policy itself. Depending on the complexity of the policy, this group may or may not play a major role in policymaking. Adjacent to them are politicians who, once elected, are the creators of policy. The next (shaded) ring, contains advocates who either support or oppose a policy, or who desire a particular rendition of a policy. I have highlighted this ring because it contains the main actors of the #commoncore story, and I will return to it in a moment. The final ring of the semi-circle is the general public. The rings are depicted as dotted lines to signify that the relationships and flow of information among these layers of the process are porous. All of these rings together contribute to the policy making process, for they all exert pressure and inform the development of policy in different ways and by different means.