#Commoncore Part 1

Prologue

Fueled by impassioned social media activists, the Common Core State Standards have been a persistent flashpoint in the debate over the direction of American education. In this innovative and interactive website we explore the Common Core debate on Twitter. Using a distinctive combination of social network analyses and psychological investigations we reveal both the underlying social structure of the conversation and the motivations of the participants. The central question guiding our investigation is: How are social media-enabled social networks changing the discourse in American politics that produces and sustains social policy? To see how the site is organized, click HOW TO USE THIS SITE.

About the #commoncore Project

In the #commoncore Project, authors Jonathan Supovitz, Alan Daly, Miguel del Fresno and Christian Kolouch examine the intense debate surrounding the Common Core State Standards education reform as it played out on Twitter. The Common Core, one of the major education policy initiatives of the early 21st century, sought to strengthen education systems across the United States through a set of specific and challenging education standards. Once enjoying bipartisan support, the controversial standards have become the epicenter of a heated national debate about this approach to educational improvement. By studying the Twitter conversation surrounding the Common Core, we shed light on the ways that social media-enabled social networks are influencing the political discourse that, in turn, produces public policy.

The Rise of Social Media-Enabled Social Networks

We live amidst an increasingly dense, technology-fueled network of social interactions that connects us to people, information, ideas, and events, which inform and shape our understanding of the world around us. In the last decade, technology has enabled an exponential growth in these social networks. Social media tools like Facebook and Twitter are engines of a massive communication system in which a single idea can be shared with thousands of people in an instant.

Twitter, in particular, represents a compelling resource because it has become a kind of “central nervous system” of the Internet, connecting politicians, journalists, advocacy groups, professionals, and the general public in the same social space. Twitter users can share a variety of media, including news, opinions, web links, and conversations in a publicly accessible forum.

In this project, we use data from Twitter to analyze the intense debate surrounding the Common Core. The standards have consistently generated a high volume of activity on Twitter. Hashtags (#) are used on Twitter to mark keywords or topics of interest to users, and hashtags related to the Common Core – in particular, #commoncore, #ccss, and #stopcommoncore (the three from which we drew our analyses) – have consistently generated 30,000-50,000 tweets a month. While topics tend to trend and fall on Twitter, debate using these three hashtags has consistently maintained this volume of activity over the 32 months from September 2013 through April 2016.

Social Network Analysis Makes the Invisible Visible

To understand the Common Core network and the discussion coursing through it, our research combines social network analysis and linguistic analysis to produce a distinctive combination of lenses that allow us to examine the debate both from the outside in and from the inside out. Pairing social network analysis and linguistic analysis gives us a unique vantage point to gain insight into the ways in which social media-enabled social networks are producing and disseminating the political discourse that influences public policy.

The powerful thing about social network analysis is that it makes visible the patterns of communication in social networks that are otherwise invisible to either those interacting within the networks or to those observing them from the outside. Regardless of whether they are networks of neighbors talking across backyard fences, friend networks on Facebook, or professional networks in business, social networks are mostly invisible to the naked eye. Despite being unseen, the ideas, opinions, and information streaming through these networks can be very consequential, both in terms of the content and with whom it is being shared. These sources help form our beliefs and opinions, which form the basis for our convictions and subsequent actions.

Looking closely at the Common Core tweets using linguistic analysis is similarly revealing. By examining how participants articulate and frame the Common Core reform and related issues, how they craft metaphors to represent their views, and what lexical choices they make, we gain insight into the psychology which motivated their participation in the conversation. Linguistic analyses can provide a deeper understanding of participants’ underlying motivations, their levels of conviction, and even their state of mind. We can conduct linguistic analyses on individual tweets, the body of activity of particular actors, and even social groups, in order to better understand how interest groups build coalitions in the social media era.

How Our Story Is Organized

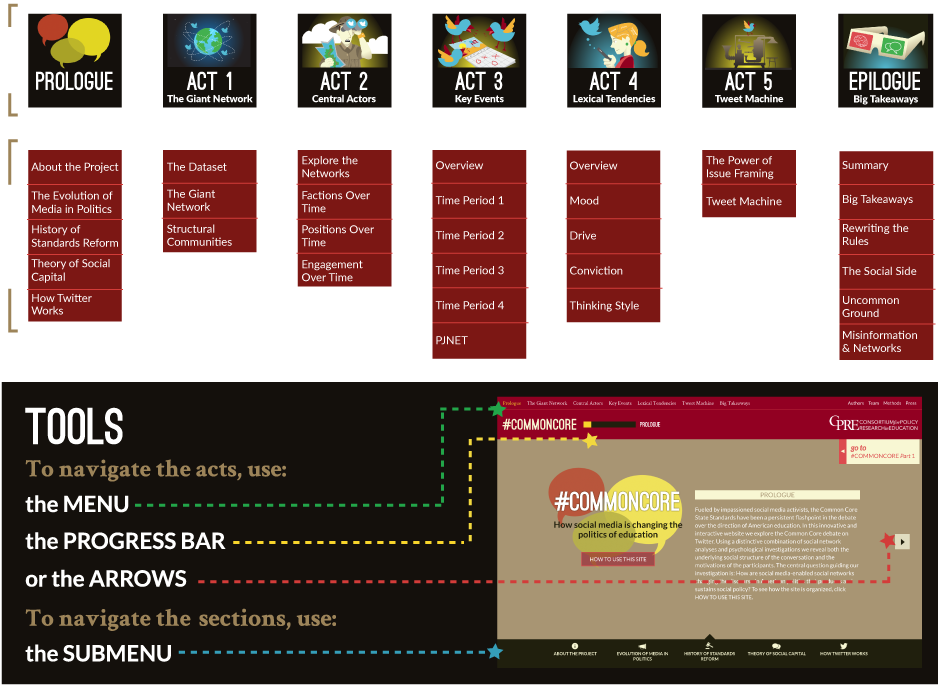

By investigating the Common Core debate through the lenses of both social network analysis and linguistic analysis, our project is based on almost 1 million tweets sent over two and a half years by about 190,000 distinct actors. This website is organized into a prologue, five acts, and an epilogue.

- The Prologue includes this overview of the project and our key findings, as well as brief primers on the evolution of media in politics, a short history of standards-based reform, an introduction to the theory of social capital upon which social network ideas are based, and an explanation of the way Twitter works.

- Act 1, The Giant Network, reveals the entire giant #commoncore social network on Twitter, made up of about 190,000 participants. Using cutting edge social network analytic techniques, which connect people based on their behavioral choices, we identified five distinct factions involved in the Twitter debate.

- Act 2, The Central Actors, disentangles the giant network and shows that most of the participants were casual contributors – almost 95% composed fewer than 10 tweets in any given six-month period. Focusing on the most prolific actors, we found that opponents of the Common Core from outside of education came to account for more than 75% of the most active participants.

- Act 3, Key Events, identifies what was driving the major spikes in #commoncore-related Twitter activity. Some of the surges were based on real events, while others were driven by outright fake news stories. There was also a growing presence of a conservative grass-roots network, which used a customized tweeting robot to send messages from the Twitter accounts of thousands of assenting users, creating the impression that disconnected participants were spontaneously tweeting about the same topic when in fact they were part of a well-organized campaign.

- Act 4, Lexical Tendencies, employs innovative large-scale text mining techniques to analyze the linguistic tendencies of the Common Core factions. This analysis examined tweeters’ psychological moods, drives, levels of conviction, and thinking styles. Common Core supporters, for example, used words that reflected high levels of conviction, tended to use more achievement-oriented words, and used words that reflected an analytic thinking style. By contrast, opponents of the Common Core from outside of education used more affiliation-oriented language, words associated with a narrative thinking style, and words that reflected the lowest level of conviction.

- Act 5, The Tweet Machine, allows participants to feed tweets into the tweet machine to learn about different frames that Common Core opponents used to appeal to the values of particular subgroups. The government frame, for example, portrays the government as controlling children’s lives through the Common Core, an argument that raises the ire of conservatives who oppose government encroachment into citizens’ privacy. Using particular frames to tap into the values of different constituencies helps to explain how the Common Core developed a strong transpartisan coalition of opposition.

- The Epilogue, The Big Takeways, includes a summary of the major insights that come from both the social and psychological perspectives, and individual essays from each of the project’s authors, which each discuss some of the important implications of this work. These include Rewriting the Rules of Engagement by Jonathan Supovitz; The Social Side of Social Media by Alan J. Daly; Misinformation and Networks by Miguel del Fresno; and Common Ground on Uncommon Ground by Christian Kolouch.

Funding

This project received funding support from the Milken Family Foundation, the Gates Foundation, and the Consortium for Policy Research in Education. The analyses, findings, and conclusions are the authors’ alone.

About the Authors

The creators of the #commoncore Project are:

- Jonathan Supovitz, the co-director of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education and a Professor of Education Policy and Leadership at the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Alan Daly, the Chair of the Department of Education Studies and a Professor of Education at the University of California, San Diego.

- Miguel del Fresno, a lecturer at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) in Madrid, Spain and a senior communication consultant and researcher.

- Christian Kolouch, a research specialist at Consortium for Policy Research in Education at the University of Pennsylvania.

Citation

Supovitz, J., Daly, A.J., del Fresno, M., & Kolouch, C. (2017). #commoncore Project. Retrieved from http://www.hashtagcommoncore.com.

The Evolution of Media in Politics

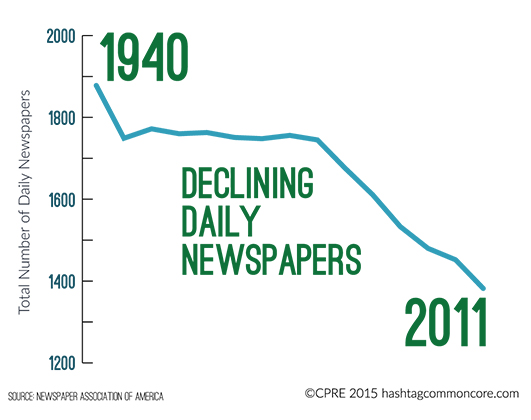

The role of the media in shaping political opinion has changed dramatically over the past 60 years, as the populace has grown both more sophisticated and more fragmented. Before World War II, radio and newspapers were the dominant forms of mass communication. Franklin Roosevelt's famous fireside chats were a central means of messaging, and newspaper circulations were at an all-time high. In the 1950s, researchers Paul Lazarsfeld and Elihu Katz observed that mass media influenced opinion leaders, who in turn influenced their followers, the general public.1 They called this process the two-step flow model to indicate that public opinion was developed through a cascading process.

As network television became more dominant in the 1960s and 70s, the three major networks—CBS, NBC, and ABC—molded public perceptions to an unprecedented degree in what became known as agenda setting. In one famous study that was replicated many times, McCombs and Shaw demonstrated the overwhelming alignment between what residents in Chapel Hill, North Carolina thought were the most important election issues of the day and what the news media reported were the most important issues. 2 The public depended heavily on the three dominant networks to stay abreast of national and international news, and because of this, the media had tremendous influence in molding public opinion.

Proliferation of Media Outlets

With the advent of cable television in the 1980s, the proliferation of channels led to a fragmentation of audiences. Cable news, talk radio, and 24-hour all-news outlets competed for attention with increasingly brazen and partisan reporting. The wide array of available media choices increasingly caused audiences to fracture as people tended to avoid information that diverged from their worldview, instead seeking out information that was consistent with their preexisting attitudes and beliefs.3 In this context, it is not hard to see why many political scientists have argued that the expansion of available news sources has increased political polarization.4

In today’s media landscape, the Internet and social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook provide even more opportunities for audiences to splinter as members with similar views have increasing access to each other. And there are some distinct differences between the media landscape at the end of the last century and the social media era we are in today. The growth of cable television in the 1980s and 1990s was still essentially unidirectional from “elites” to general audiences because of the content control of mass media and passive forms of viewing. Social media, however, allows members to actively voice their opinions and engage directly with each other.

Some researchers, including Valenzuela, Park, and Kee, view social media as a new opportunity for political participation, free flow of information, and broader democratic mobilization.5 Others, like Roodhouse, view social media sites as nothing more than discursive information flows and echo chambers where the fervent can shout with each other.6

Thus, Twitter is in many ways the perfect platform for examining the ways in which social media are influencing the Common Core conversation in the United States. Twitter is a free, online, and global communication network that combines elements of blogging, text messaging, and broadcasting. One of the most valuable aspects of Twitter is its evolving nature to be, "a media of intersection of every media and medium."7

References

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. & Katz, E. (1955). Personal influence. New York: Free Press.

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36 (2), 176-187.

- Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative vs. participatory democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58(4), 707-731.

- Valenzuela, S., Park, N., & Kee, K. F. (2008). Lessons from Facebook: The effect of social network sites on college students’ social capital. In 9th International Symposium on Online Journalism, Austin, TX . Retrieved from https://online.journalism.utexas.edu/2008/papers/Valenzuela.pdf

- Roodhouse, E. A. (2009). The voice from the base(ment): Stridency, referential structure, and partisan conformity in the political blogosphere. First Monday, 14 (9).

- Dorsey, J. (2012). “Twitter takes the pulse of the planet. It’s the intersection of every media & medium,” Twitter, November 15, 2012. Retrieved from http://twitter.com/TwitterAds/status/269129576318386177

The Recent History of Standards Reform in America

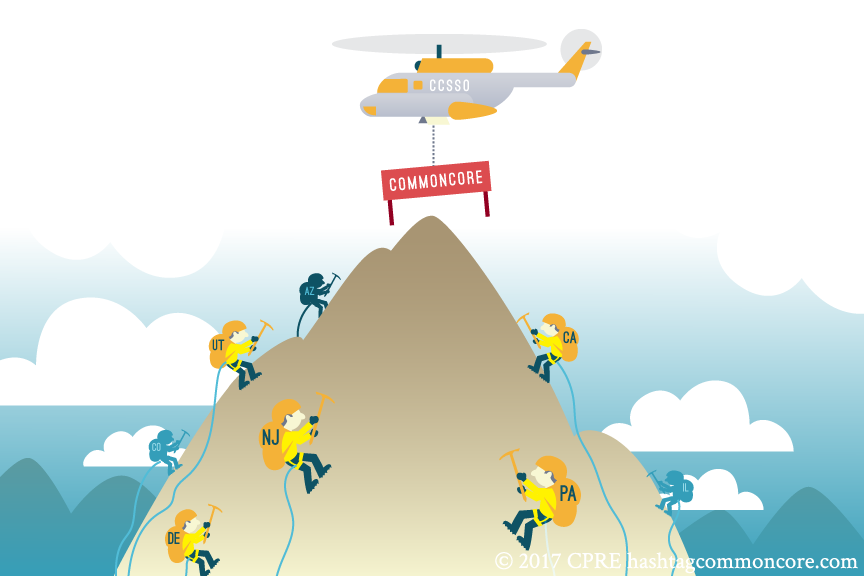

The Common Core State Standards set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level. The standards were developed at the behest of a group of organizations led by the National Governors Association (NGA) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The development of the Common Core began in 2009, but the standards are part of a history of several decades of education reform.

1980s: Focus on Minimum Competency Testing

In the 1980s, policymakers created a set of minimum competency tests, which they intended schools to use as a foundation for performance. The expectations codified in the tests focused on a set of basic skills that schools were expected to have all students meet. However, the basic expectations assessed through the minimum competency tests often became the aspirations for instruction. The important lesson from this era was that low expectations produced low performance.

1990s: Statewide Systemic Reform

The apparent "race to the bottom" phenomenon spurred by minimum competency testing led to an emphasis on high expectations. The systemic reform effort of the 1990s was built around three general principles. First, ambitious standards developed by each state would provide a set of targets of what students ought to know and be able to do at key grade junctures. Second, states measured progress toward standards by developing aligned assessments that combined rewards and sanctions for holding educators accountable to the standards. The third component was local flexibility in organizing capacity to determine how best to meet the academic expectations.1 This structure of clear goals (standards), measures (assessments), and incentives (accountability) at the state level, combined with implementation autonomy, fit with our historical conceptions of education as a local effort. This led each state to develop its own standards and assessment systems, which produced lots of variation in the quality and rigor of state educational systems across the country.

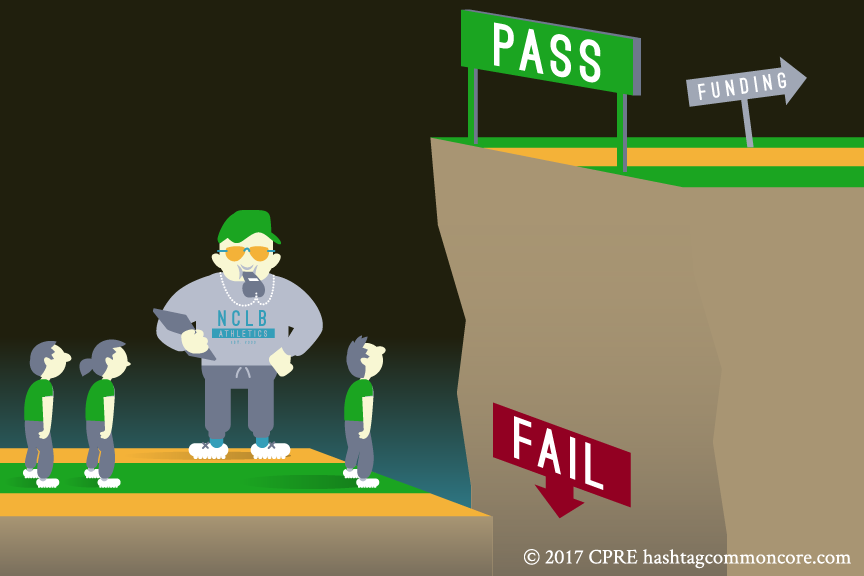

2000s: Test-Based Accountability

The 2000s gave rise to the era of test-based accountability in education. The 2001 passage of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act inaugurated an expansion of testing by requiring states that received federal funding to assess students in all grades between third and eighth, and one year in high school. NCLB pressed states to develop plans to have all schools make adequate yearly progress with a target of 100% proficiency by 2014—an endeavor that would prove to be impossible. The NCLB legislation also required states to disaggregate school results by subgroups, in an effort to prevent districts and schools from hiding disparities in performance within overall averages. This movement can be seen as an attempt to tighten the linkages in the theory of standards-based reform by increasing student performance expectations via high-stakes testing to hold schools accountable for meeting standards.

Research on schools pressed by test-based accountability showed both productive and unproductive responses. There was an increase in attention to tested subjects, a rise in test preparation behavior, more attention to students just at the cusp of passing the test, and greater attention to heretofore marginalized students.2

Some states also gamed the system by creating tests that most students could easily pass. There were also several cases of systematic cheating by educators in school districts and schools that made national headlines. The accountability emphasis of No Child Left Behind left many policymakers convinced that although pressure was important, we couldn't just squeeze higher performance out of the system—we had to build a structure to support it.

2010s: “Common Core State Standards”

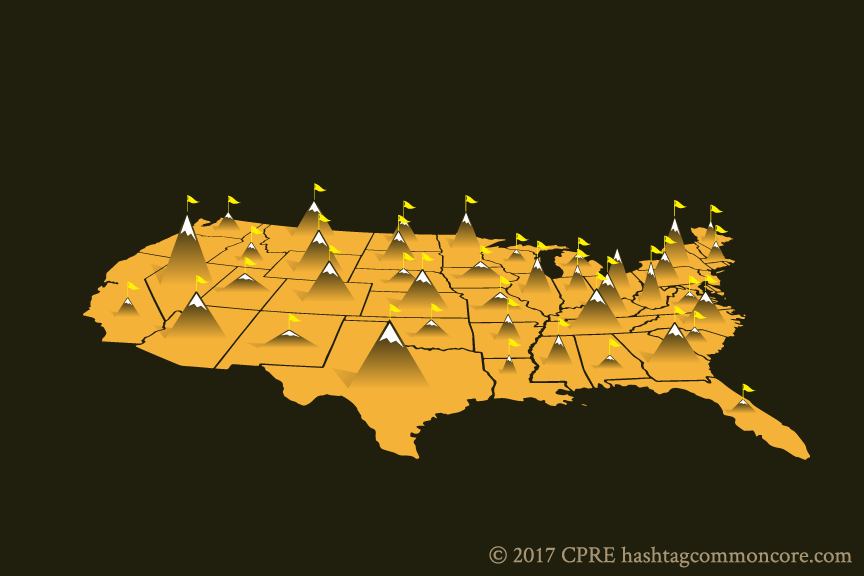

This brings us to the present major reform initiative in the United States - the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The CCSS set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level from Kindergarten to 12th grade. In a remarkable moment of bi-partisanship, the CCSS were adopted by the legislatures in 46 states and the District of Columbia in 2010. Alaska, Texas, Virginia and Nebraska did not adopt the Common Core, preferring their own state standards. Minnesota adopted the Common Core ELA standards, but not those in mathematics. Since then, the CCSS have become remarkably political and several states have either backed away from the CCSS and/or the associated tests or are in the midst of heated discussions about their involvement with the CCSS.

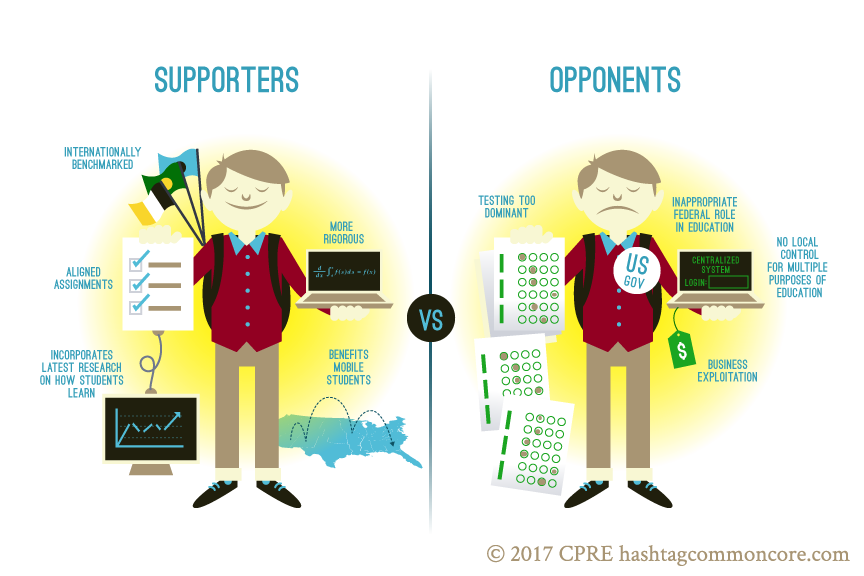

The CCSS incorporate a number of lessons learned from the earlier standards-based reform movement. The new standards were named the "Common Core" because they were intended to eliminate the variation in the quality of state standards experienced in the past. The experience of the 1990s taught us that not all standards are equal. The new experiment with common state standards was done to avoid the previous problem of differing quality of standards and their accompanying student assessments. They were developed at the behest of the state governors and chief state school officers to avoid the charge of federal intrusion—which came nonetheless after the Obama administration advocated for the CCSS in the Race to the Top funding competition and provided the financing for the Common Core testing consortia. Similarly, the Common Core testing consortia of Smarter Balanced and Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) were funded to create assessments aligned with the standards. Thus, there was a push for a uniform set of standards and the development of aligned assessments to build a more coherent system for educational improvement.

In sum, many factors led to the development of the Common Core State Standards. Ever since the Nation at Risk Report of 1983, which famously stated "the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people," we have felt our education system besieged.3 Flat longitudinal performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and middling performance on international comparative assessments like TIMSS and PISA has further perpetuated the belief that America needs a more rigorous education system to compete with other nations in the increasingly global economy. This middling performance is often partly attributed to the spiraling nature of what is taught in America's schools, a student experience that has been called "a mile wide and an inch deep."4

Thus, the Common Core represents the latest response to the challenge of educational improvement by incorporating the lessons learned from prior experiences with education reform. The minimum competency era taught us that we needed high expectations for all students. The state-wide systemic reform movement of the 1990s taught us that state-led standards and testing systems would produce too much variability in quality and alignment. The decade of experimentation with test-based accountability drove home the lesson that, while accountability pressure was important, we couldn’t just squeeze higher performance out of the system without a coherent infrastructure to support it. All these factors have led to the push for a more comprehensive system with a uniform set of standards and aligned assessments that would allow for consistency in an increasingly mobile society.

Ongoing Controversy Surrounding the Common Core

Since their bipartisan adoption in 2010, the CCSS have become increasingly controversial. A series of important events contributed to both the pace of implementation and policymaker and public perceptions of the CCSS. First, the severe economic recession of 2008 spurred the economic stimulus of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009, which included funding for the Race to the Top (RTTT) competition in education. Forty-six of the 50 states submitted applications for RTTT (Alaska, North Dakota, Texas, and Vermont did not submit applications), which included a provision that states adopt rigorous standards, and eventually awarded over $4.1 billion to 19 states. This financial carrot heavily incented states to adopt the CCSS, but created an impression of Federal coercion.5

Second, by 2013, more than half the governors who were in office when their states adopted the standards (and who were members of the National Governors Association, a sponsor of the CCSS) were no longer in the governorship, loosening states’ commitment to the standards. There was also growing partisan resistance in several states about continuing to use the CCSS. In 2013, Republican legislators in 11 states introduced legislation to repeal adoption of the Common Core.6 In 2014, Indiana, Oklahoma, and South Carolina backed out of the CCSS and several other states (including Missouri, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and West Virginia) have modified their standards to replace the Common Core. Additionally, about half of the states have withdrawn from the associated Common Core aligned test consortia.

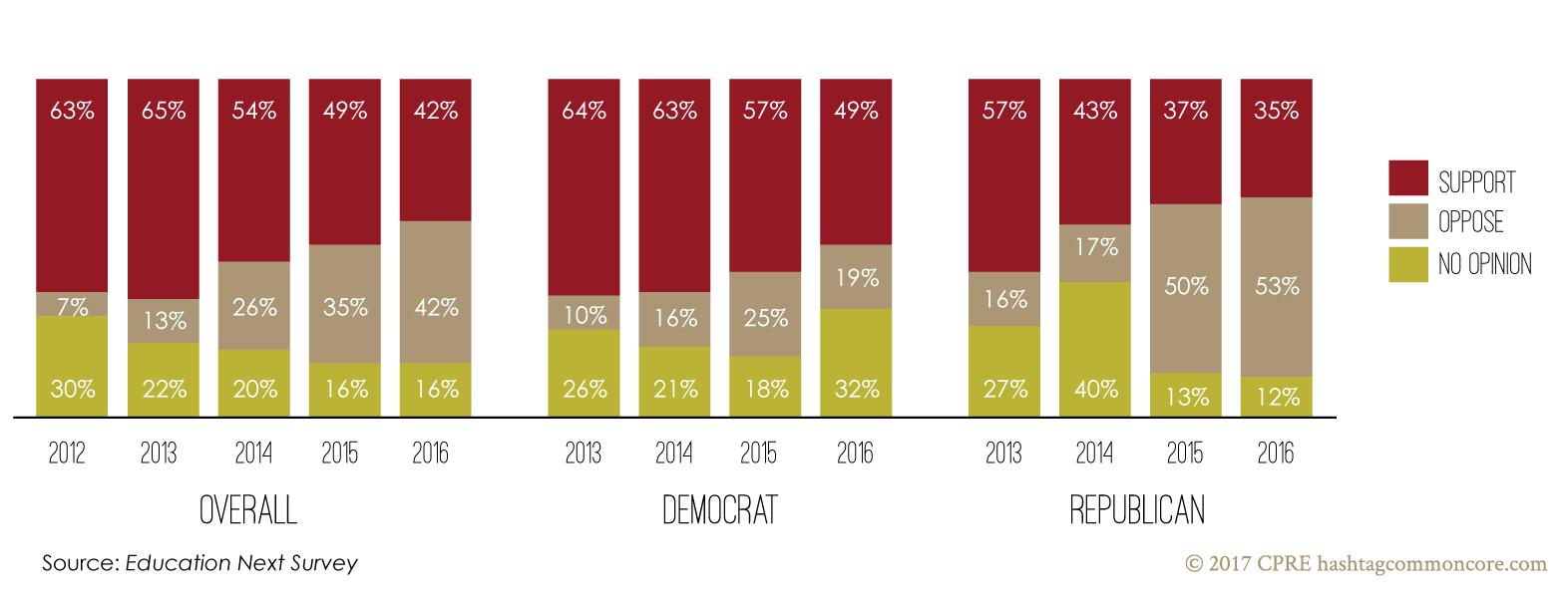

Third, as shown in the Education Next survey results, the CCSS have become increasingly unpopular and partisan. In 2012, 63% of respondents supported the CCSS. From 2013 to 2015, support declined from 65% to 49%. At the same time, while Democratic support remained in the low 60% range, Republican support declined 20 percentage points, from 57% to 37%. The ongoing controversy surrounding the CCSS provides both a backdrop and consequence of the activity on Twitter.

References

- Smith, M. S., & O'Day, J. A. (1991). Systemic school reform. In S. H. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing: The 1990 yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (pp. 233-267). New York: Falmer Press.

- Hamilton, L. (2003). Assessment as a policy tool. In Robert Floden, (Ed.) Review of Research in Education, 27, 25-68.

- Gardner, D. P., Larsen, Y. W., Baker, W., & Campbell, A. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Schmidt, W. H., McKnight, C. C., Houang, R. T., Wang, H., Wiley, D. E., Cogan, L. S., & Wolfe, R. G. (2001). Why schools matter: A cross-national comparison of curriculum and learning. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

- McDermott, K. A. (2012). "Interstate Governance of Standards and Testing." In Education Governance for the 21st Century, eds. Paul Manna and Patrick McGuinn. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. 130-55.

- McGuinn, P., & Supovitz, J. A. (2016). Parallel play in the education sandbox: The Common Core and the politics of transpartisan coalitions.